Contributing Writer

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Defining acceptance and rejection standards for surface appearances

Tolerance for fit is easy; tolerance for finish involves judgment calls

- By Gerald Davis

- March 5, 2019

- Article

- Shop Management

Figure 1

As an example, some parts of this product are visually important. Most of the parts are hidden under covers and are not cosmetically critical.

Editor's Note: If you would like to download the visual inspection standard from Voga Coffee Inc., click here.

The topic of tolerance specification is an ongoing theme from previous episodes, with recent emphasis on making sure that reasonable dimensional tolerances appear for fabricators. “Good luck with reasonable” sings the chorus.

Tolerance for appearance—how it must look—is an equally challenging specification. When it comes to an accept or reject decision, fit and finish both matter.

Here’s a CAD tip: Product manufacturing information (PMI) can be saved as metadata in 3D models. That PMI then can be used to goof-proof the creation of 2D fabrication drawings—that is, to automatically populate their title blocks. Among other details, PMI includes dimensional and cosmetic tolerance specifications.

When a production line must produce visual consistency from batch to batch as well as from part to part, its quality control program probably will include sample coupons for comparison of finish, written instructions for use of those coupons, and training and certification for all personnel handling and shipping the product.

If the product’s specifications do not include standards for inspection of appearance, verbal instructions or assumptions must prevail. Variable appearance from batch to batch is acceptable by default.

(Let’s take a time-out before proceeding any further. This discussion causes me to reminisce about my years working as a cost estimator in a job shop. In those days, in the absence of written standards, a first-time customer’s price sensitivity was the guide for their cosmetic tolerance. If the customer said that fit and cost were the only things that mattered, we did not throw away any part because of marginal appearance. That certainly lowers the expense of cosmetic inspection. If the customer said finish mattered as much or more than fit, then every part shipped required individual buffing and wrapping. If the customer didn’t say and if I really felt like the customer was a good fit for our shop, I offered them a copy of our in-house visual inspection standard. The customer then had the opportunity to update their drawings or revise their POs to take the guess out of the work.)

Of course, every part could be manufactured to perfection; that is one form of a quality control program. Fabricators know that excessive tolerance specification leads to excessive cost of production. Beyond cost, excessive beauty represents lost opportunity. Pretty parts getting hidden in final assembly where no one will care may be charming but is sad. Conversely, failing a beauty pageant is a terrible fate for an otherwise perfect part.

Does the world need another quality assurance standard? Probably not the world, but the business network supporting the fabrication of a product requires a standard. (When accept/reject is based on a measured value, harmony exists in the supply chain. When judgment is based on feeling, discord is sown.) In a scenario where “if not yours, then mine might do,” a personalized standard allows for lingo that is tailored to the product. It literally comes down to defining what a flaw is.

Frequent readers of this column are familiar with products designed and assembled by Voga Coffee Inc. Its brewers have often appeared as models for discussion in the pages of The FABRICATOR (see Figure 1). Voga subcontracts in many fabrication trades—bent tubing, precision sheet metal, spun metal, moldings, machined gizmos, glass, and granite, for example. If you’re interested in joining its supply chain, the company has a website. Voga is kindly allowing us to examine its visual inspection standard. If you’d like to adapt it as a visual inspection standard to become your own, excluding all things specific to coffee and brewing, please feel free to do so.

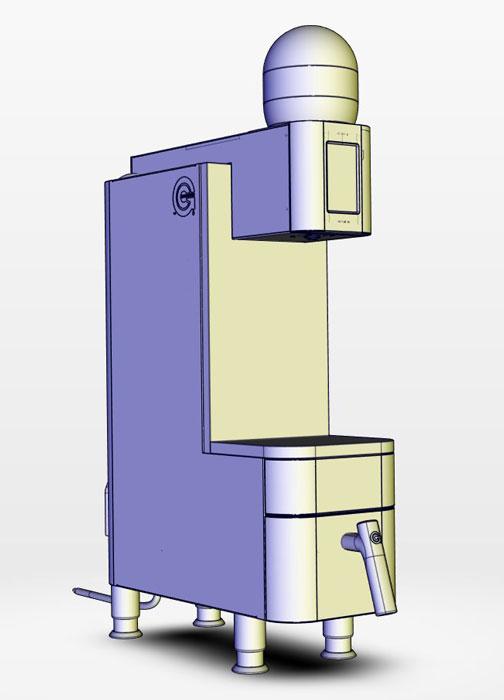

Figure 2a

An example of a visual inspection standard is shown. Its purpose, scope, and environment are tailored to inspecting the product shown in Figure 1.

Inspecting a Visual Inspection Standard

They may be hard to read, but the first couple of pages of the visual inspection standard are shown in Figure 2a. To summarize what is shown, its stated purpose is to inspect coffee brewers. The document references ASTM D3359-97 (adhesion testing with tape). The inspection environment, as defined in this standard, is typical for coffee brewers. It could be adapted to be suitable for something like farm equipment.

Limits on Distance and Time

The distance of inspection is something that Voga has agonized over. It’s important to inspect parts at a close distance, but the joke is that the marketing department likes to show up with magnifying glasses. This standard has helped keep Voga’s costs under control by banning magnifying glasses and by limiting part manipulation.

It Do What It Do

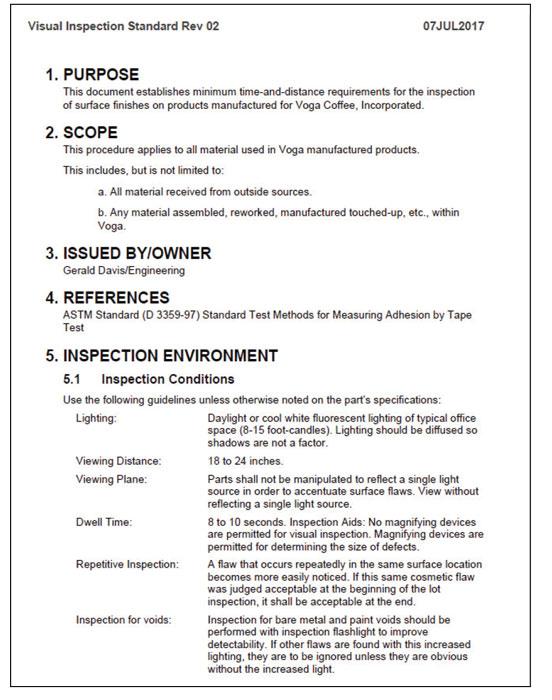

The end use of the part—hidden or visible—is hinted at by the “class” of finish (see Figure 2b). This is the most argued part of this example and other visual inspection standards. What to call the classes? This standard uses ancient roman numerals, and other, similar standards use letters as well as different categories. This QA standard is faintly similar to a document released by Hewlett-Packard in the late 1970s. It used Class II, IIA, IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC for painted parts.

In Figure 2b, the guiding light behind the Class I, II, or III is “..classes of finish are defined by how often and by how visible the surface is in the finished product.” The visibility choices are “frequently,” “occasionally,” and “never” for Class I, II, and III, respectively. The quality control department does not give a hoot about visibility; it just wants to know which column in the decision table to use.

To be clear, these three visual inspection classes are mostly for the benefit of the designers and drafters. The drawing may specify Class III for a part that is very visible. The implication for Voga’s design/drafting/marketing efforts is that Class I costs more than Class III, so select visual inspection requirements wisely.

Clean Is What I Mean

When the visual inspection is performed, the cleanliness of the part matters. This standard does not apply to clean-room parts. The term “free of dirt” is within the context of “no magnifying glasses.” We’ve had to explain that to the marketing department.

Rough by Any Other Name

To explain roughness, the standard says that Voga drawings will use Ra (as opposed to RMS, for example). The charts shown in Figure 3 often are used by designers and draftsmen to understand appropriate specifications. This plagiarism of charts is not appropriate for a commercial document. However, Voga is not selling visual inspection standards.

Clarifying It Clearly

The section on definitions is trying to clarify “common knowledge.” The use of photographs as opposed to re-creation of a dictionary (see Figure 4) has helped, particularly with international supply chains. Figure 5 is an example of a drawing referencing the Visual Inspection Standard Class III (note 6).The Matrix

All of the preceding definitions and illustrations come to bear in the decision matrix (see Figure 6) that appears near the end of the standard. Perhaps this table should have been on page one of the standard. It has columns for Class I, II, and III. Each column shows how many of what kind of flaw may be acceptable.

A purchasing department might find such a table useful as an attachment to solicitations for bid (also known as request for quote). This table by itself clarifies the 2D fabrication drawings (see Figure 5). Once accustomed to the standard, a fabricator is most likely to reference this decision matrix more than any other sheet in the visual inspection standard.

Gerald would love for you to send him your comments and questions. You are not alone, and the problems you face often are shared by others. Please send your questions and comments to dand@thefabricator.com.

About the Author

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 05/07/2024

- Running Time:

- 67:38

Patrick Brunken, VP of Addison Machine Engineering, joins The Fabricator Podcast to talk about the tube and pipe...

- Trending Articles

How laser and TIG welding coexist in the modern job shop

Young fabricators ready to step forward at family shop

Material handling automation moves forward at MODEX

A deep dive into a bleeding-edge automation strategy in metal fabrication

BZI opens Iron Depot store in Utah

- Industry Events

Laser Welding Certificate Course

- May 7 - August 6, 2024

- Farmington Hills, IL

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI

Precision Press Brake Certificate Course

- July 31 - August 1, 2024

- Elgin,