Owner, Brown Dog Welding

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Manufacturing is facing a wage gap, not a skills gap

If unemployment rate is at or above real wage growth, skills gap doesn’t qualify

- By Josh Welton

- January 14, 2020

Detroit welder and metal fabricator Josh Welton argues the common belief that the fabricating and manufacturing sectors are facing a skills gap is false. He believes the real problem in the industry lies with poor wage growth. Getty Images

Here’s a radical idea: As we continue this back-and-forth between those of us who advocate for blue-collar workers and the other groups and societies that advocate for the industry and the organizations that control it, let’s allow truth, numbers, and common sense to be our guide.

For decades we’ve heard from manufacturers, through public relations firms, industry-backed organizations, schools, and the media, spinning a tale of woe. The skilled positions vital to their operation and to the very core of our country are going increasingly unfilled.

Twenty years ago the main reason was that the average worker’s age was 55. Old-timers, the “greatest generation,” were starting to retire, and youngsters wanted to go to college instead of working with their hands. Fast-forward to today, and it’s all the same empty fluff repeated: The worker’s average age is still 55, but now it’s the boomers that are starting to retire. It’s that millennials don’t want to work, they don’t want to get their hands dirty. It’s still that too many kids are fooled into going to an expensive four-year college instead of a less expensive two-year vocational school. They’re telling the same tall tales, just updated with contemporary vernacular.

I’ve already written about how the numbers they use are bogus. That even if the average age of a skilled worker is 55 (which is a much higher estimate than what the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows), it doesn’t matter because people aren’t retiring at 60 anymore; the fastest-growing group of workers is those 65 and up. That with the cost of living increasing and real wages remaining stagnant at best, they can’t afford to retire. That, while some trades (especially those requiring a four-year apprenticeship) are growing at a rate nominally faster than the national average, welding as an occupation is actually growing below the national average. That it is impossible for our industry to add the number of new jobs into the economy as they’ve tried to sell us on.

All of this went unchallenged for a long time because, hey, what’s wrong with spreading the word about welding? They’re showing a path to careers available to non-college graduates. And if that’s all it was, you wouldn’t hear a negative word from me. I love welding. I love all the processes, the fire, the smell, the satisfaction that only burning in that perfect bead can bring. It’s opened a lot of doors for me. But the reality is that if you want to make it in this trade, you need to want it.

Doing it for money or for job security will disappoint you more often than not. Skilled jobs aren’t falling off of trees, and production work doesn’t pay. Instead of sketching a fair picture of the challenges welders young and old alike will face, the AWS, the national media, certain welding schools, and the manufacturers inundate us with ads, blogs, and articles about how hundreds of thousands of jobs (if not millions) are coming in the next decade; how pay is “often” in the six figures, how starting salaries for new welders are more than those for jobs that require fancy diplomas; how managers, supervisors and HR departments just cannot find enough qualified candidates. And to top it off, they’re asking we the taxpayers to help foot the recruitment and training bill because, you know, the country needs skilled labor.

The problem I have is that because of these incessant efforts, the idea of America having a “skills gap” crisis, and all that entails, is now ubiquitous despite being false.

Defining a skills gap based on what employers say isn’t enough. That’s like the fox telling the farmer he’s not keeping enough chickens in the henhouse, and the farmer telling the chickens the henhouse is heaven.

I’ve tried to put it into my own words before, but now for the sake of precision and clarity, I’m going to quote from Heidi Shierholz and Elise Gould of the Economic Policy Institute. I’ve bolded certain portions for emphasis:

“We certainly hear widespread employer complaints about not being able to find workers. Why? One reason is monopsony power in the U.S. labor market. There is a lot of evidence that many firms have monopsony power, either because of a limited number of buyers of labor or other sources beyond labor market concentration. When firms have monopsony power, they are able to pay workers less than what their work is “worth,” i.e., less than their marginal product. But a key dynamic of monopsony power is that even though monopsonists would like to hire more workers, the low wages they offer mean they can’t attract more workers unless they pay more. That is, it is a normal state of affairs for a firm with monopsony power to wish they could hire more workers at the wages they are offering, but to be unable to attract additional workers because their wages are too low. So when a firm with the power to set wages below a worker’s marginal product complains about not being able to find workers at the wages it is offering, it’s useful to remember that it is choosing to keep wages low in order to increase profits—which remain high as a share of corporate sector income—and could get more workers by simply raising wages. And importantly, when firms with monopsony power complain about not being able to find workers, it is not adequate evidence of a skills shortage. What would be good evidence of a skills shortage? The footprint of a bona fide shortage of workers with certain skills is a low number of available workers with those skills combined with unusually strong wage growth for workers with those skills.”

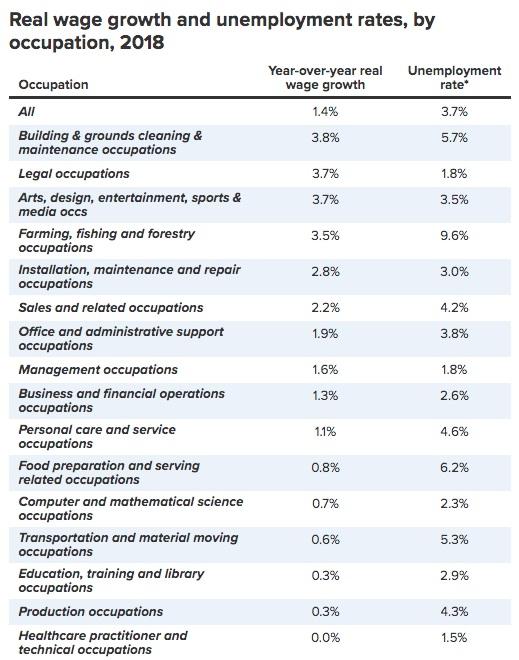

By these standards, you will have a skills gap only when real wages for a given job are increasing well beyond the unemployment rate for that job, and that’s simply not happening. Companies have not drastically increased wages and benefits. They aren’t short workers, they’re short workers willing to take the same sluggish pay they’ve been offering for half a century.

In this graphic from the Economic Policy Institute showing a sample of occupations, only the legal occupation category is close to qualifying as a skills gap. If the unemployment rate is at or above real wage growth, it doesn’t qualify. Economic Policy Institute

Words have meaning. Numbers, in the proper context, matter. Look at the sources and come to your own conclusions.

I’m still working on a resolution. I do know filing into the henhouse isn’t it.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscriptionAbout the Author

- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI