Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

The business case for investing in high-powered laser cutting

Why Tennessee-based shop Cupples’ J&J Co. pushes the fabricating technology envelope

- By Tim Heston

- Updated October 15, 2023

- October 13, 2023

- Article

- Laser Cutting

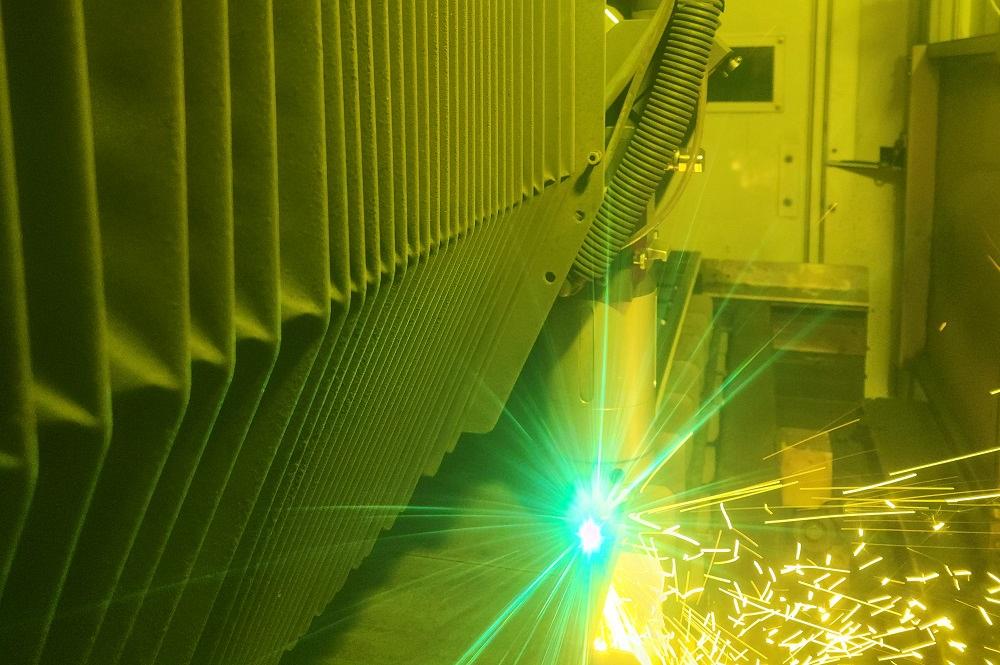

Cupples’ J&J Co.’s 30-kW fiber laser slices through 3/4-in. hot-rolled pickled and oiled material at 228 IPM.

Editor’s Note: This in-depth look at high-powered fiber laser cutting at Cupples’ J&J Co. Inc. in Jackson, Tenn., is the first in a two-part series.

Years ago, whenever I visited a precision sheet metal shop, someone would boast about the cutting speed, the inches per minute (IPM) they were achieving with that 2-, 3-, or 6-kW CO2 laser system. Then the fiber laser came along. Talk of jaw-dropping IPM figures burst forth—then quieted down.

Everyone soon realized the fiber laser cut thin sheet so quickly that it outpaced everything else on the machine, including the pallet tables and drive systems. Downstream bottlenecks became a problem too. What good is extraordinarily fast cutting if it creates a denesting bottleneck?

Jeff Cupples, though, still quotes IPM numbers all the time, but he’s not talking about cutting gauge material. He’s talking about plate—thick plate. For decades, he’s helped build a custom fabricator well known in laser cutting circles for pushing the envelope. At this writing, Jackson, Tenn.-based Cupples’ J&J Co. has 24 laser cutting machines, including two 30-kW systems and a 40-kW system on the way, complete with bevel cutting.

The shop is now cutting 3/4-in.-thick steel at a pace similar to the speeds it cut 11-ga. sheet two decades ago—at 225 IPM or more. As we walked through the plant’s high-powered laser cutting area, Cupples pointed to various parts, all cut cleanly, with no dross or deep striations. “We cut that 5/8-in. material at 290 IPM. And we could cut it faster, but that’s a production part, so we’ve dialed it back a bit.”

Cupples focuses on speed but has a careful eye on overall process reliability and consistency. He and the team scrutinize the entire process, from loading the plate to denesting and edge quality inspection. With all the company’s laser cutting power, it has no flat-part deburring, deoxidizing, or leveling machine. Even long or oddly shaped parts emerge clean and stack flat, no part leveling required.

Driving the fabricator’s success has been those dramatic reductions in overall processing time. One ¾-in. job the company fabricated two years ago took over two hours to make with a 6-kW CO2 laser cutting machine. Today, a nest of those parts is cut on an ultrahigh-powered fiber laser in just over 19 minutes, denested quickly, then sent directly to robot welding.

That time savings opens a world of possibilities in a fabrication market benefiting from increased infrastructure and industrial spending. In effect, those envelope-pushing efforts are helping Cupples’ J&J stay ahead in a fast-growing niche: precision plate fabrication.

How Cupples’ J&J Evolved

Cupples’ father James (one of two “James” who in 1966 founded the company, hence the J&J moniker) moved to the current location in Jackson in 1979. At that point, Cupples’ J&J was a small machine shop. When machinery broke at local processing plants, Cupples was called on to deliver machined parts in a hurry. By the early 1990s, the company had dipped its toe into precision metal fabrication, and by the late 1990s, the fabrication business started to explode. Today, sheet and plate fabrication comprise more than half of the fabricator’s revenue, and much of that involves parts with machined components.

In the precision fab arena, the company has become well known for its high-powered lasers, but it still processes the gamut of grades and thicknesses, from gauge material on up. It has a large plasma table and a 95-KSI waterjet for specialized jobs or workpieces that can’t tolerate a heat-affected zone.

(From left) Jeff Cupples and Mike Etheridge, laser technician, stand by the company’s 30-kW fiber laser from Cutlite Penta. Cupples’ J&J Co. has worked closely with various machine vendors over the years to push the technological envelope.

“We’ve been heavy into food processing equipment for decades,” Cupples said, “along with anything that goes in the garage, mows the grass, or moves the dirt. Those are good, basic mainstay industries for us.”

Several years ago, the company’s management team moved into a facility across the road from one of its main plants. To the east, the fabricator has gradually acquired acres of land. The original machine shop sat on a 4-acre plot. Today, the organization owns more than 80 acres, all soon to be zoned for industrial use. Already one of the largest contract metal fabricators in the country, Cupples’ J&J has quite the runway for even further growth.

The Ripple Effects of Precision Plate Cutting

Back in the CO2 laser days, many thought that a material thickness of little beyond 1 in. was laser cutting’s practical limit, considering the shape of the beam and its depth of focus. When fiber lasers came on the scene in the late 2000s, everyone saw them as machines good for thin sheet cutting. Want to cut thick? Stick with the CO2 machine.

How times have changed. Ultrahigh-power fiber lasers—with their wide beams, extraordinary power density, advanced cutting heads, controlled gas flow, and sophisticated nitrogen-oxygen assist gas mixing and delivery—have blown those assumptions out of the water. Today, Cupples’ J&J has tested cutting 1.5 and even 2-in.-thick plate, delving deep into precision plasma’s territory.

Pushing the laser cutting envelope doesn’t come without risk. Several years ago, as fiber lasers offering 12 kW and beyond hit the market, Cupples’ J&J jumped in as an early adopter and experienced its fair share of headaches. “We blew about 14 heads over a period of 10 months,” Cupples said, adding that the company has had to endure long periods of down machines waiting to be serviced. “I can’t help it. I’m a mechanical engineer. If I can’t break it, it will work. So we will try to push technology to the edge of what it can do.”

He’s communicated continually with laser cutting machine vendors over the years, including TRUMPF, Bystronic, Eagle, and, most recently, Cutlite Penta. Machine techs have spent a good amount of time at Cupples’ shop, which has turned into a kind of “real-world” testing lab for the bleeding edge in fiber laser cutting, especially for plate material.

This all might sound a tad quixotic. All that machine downtime doesn’t come cheap. Also, such heavy-plate cutting is difficult to automate. Wielding magnets and sometimes hammers (though most parts have perfected kerf geometries so that they lift out easily), operators need to take those heavy parts out of a cut nest by hand. Even with all its lasers, the fabricator relies on shuttle tables and manual parts offloading.

Look downstream, though, and you begin to see what employees call “the Cupples way.” The operation has 39 press brakes, many grouped strategically near a high-powered laser. Some brakes are new, with multiaxis backgauges and all the bells and whistles. But some are retrofitted with new CNCs and bed surfaces remachined to eliminate any ram upset and ensure forming accuracy. (“We’re a machine shop,” Cupples said. “We can machine those [brake bed surfaces]. It’s what we do.”)

Some have X-axis stops with fingers fitted with precision-laser-cut templates, contoured for specific parts that otherwise couldn’t be bent productively on a brake with such a simple backgauge. Operators aren’t spending hours struggling to set these machines up, either. The brakes might be old, but they’re well maintained, have quality tooling, and are set up to form specific jobs with specific material from a specific service center and mill. Cupples’ J&J scrutinizes the material it buys (including some very thick hot-rolled pickled and oiled stock), monitoring its strength, surface quality, and overall consistency—and both laser cutting and forming benefit from that.

Cupples has plenty of machining capabilities, so the forming areas have racks of custom tools, from special offsets to radius forms. It also has an extensive rack of laser-cut check fixtures. Operators form pieces, place them in the check fixture, then move on to the next piece. The same goes for rolling. An operator initiates a rolling sequence, measures the previously rolled part in a check fixture as the plate roll finishes its cycle. She then retrieves the next rolled piece. It’s a ballet of carefully choreographed efficiency.

The corporate office sits across the street from one of the main plants in Jackson, Tenn., offering fabrication and screw machining. Behind this plant are several fabrication and machining facilities—and plenty of open acreage for future expansion. Another Cupples’ J&J plant is in Dyersburg, Tenn.

Walk down to welding, and you see rows of welding robot cells adjacent to a long rack full of fixtures, all made in-house. Here is where machined parts and fabricated plate come together. And seeing just how quickly and smoothly these components come together reveals the reason behind Cupples’ quest for ultrahigh-power laser cutting precision.

Cupples pointed to one 5/8-in.-thick plate, staged for fixturing near a robot weld cell. “See that? There’s less than a 0.005-in. taper on that cut edge. We couldn’t achieve that even with our ultrahigh-definition plasma. We used to plasma cut this, then send it to machining. Now, it’s done-in-one in laser cutting.”

The cutting process feeds everything else, and the more dialed in that cutting is, the more efficient the entire operation becomes. Pushing the envelope isn’t easy, but the payoff can be seen throughout Cupples’ shop. Jobs flow out the door; on-time delivery rates remain nearly perfect (well above 95%). All that productivity has allowed Cupples to invest aggressively while still being financially conservative. “We own every machine we have,” Cupples said, “and we pay cash for new machines we buy.”

Far from quixotic, it turns out that Cupples’ J&J isn’t chasing windmills after all.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

JM Steel triples capacity for solar energy projects at Pennsylvania facility

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI