Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

One metal fabricator’s holistic automation strategy

Lincoln, Neb.-based Metalworks Inc. focuses on culture and consistency

- By Tim Heston

- September 6, 2023

- Article

- Automation and Robotics

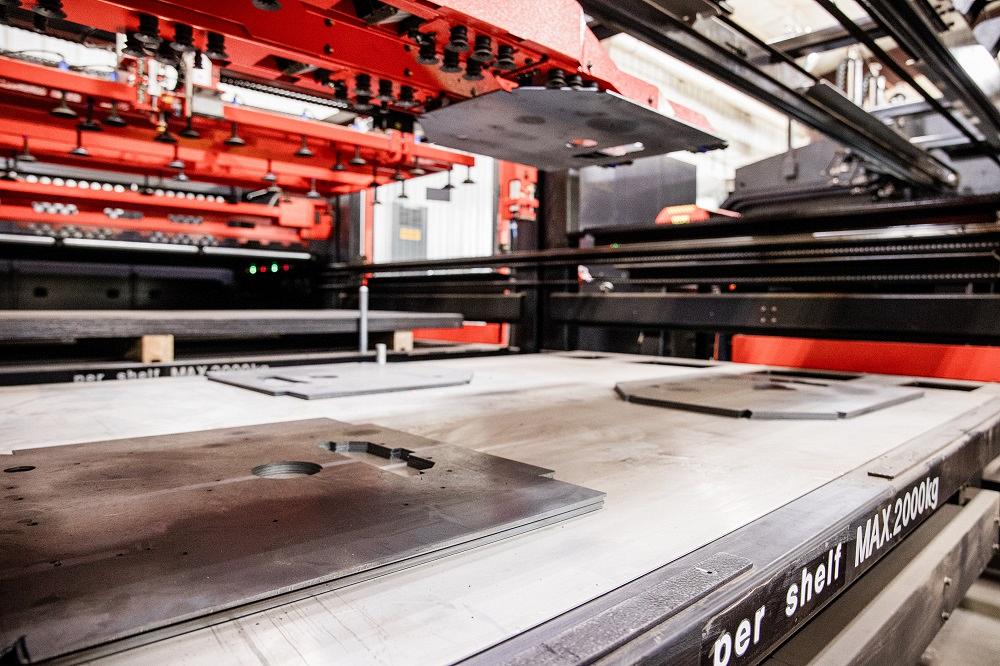

A technician at Metalworks inspects and maintains its blank unloading automation from a laser cutting system.

At Metalworks Inc.’s main plant in Lincoln, Neb., co-founders Rob Ernesti and Doug Swanson walked past a new punch/laser system being tested, complete with part removal and stacking automation. It’s one piece of a value stream dedicated to a family of parts. They next walked by a row of small and large robotic press brake cells; a little later they came across a collection of welding robots. After that, Ernesti paused, then said something that, on the surface, didn’t have anything to do with the merits of an automated fab shop.

“The biggest thing we manage here is our culture. Our culture is everything to us. You find out how important your employees are the day they don’t show up.”

Historically, automation and shop culture sometimes stood at odds with each other. After all, a shop culture is all about providing a quality working life to employees. Job-eliminating automation doesn’t seem to fit into that picture. Thing is, the picture isn’t that simple.

A confluence of factors spurred Metalworks’ journey into automation, especially over the past five years. First, customer demand is there but the people aren’t—a common conundrum that’s pervaded this business for years. Metalworks’ customers want the fabricator to grow its capacity, and it couldn’t do that without automation.

Still, automation isn’t about having the ability to grow without adding people, and the numbers behind Metalworks’ growth story prove it. The fabricator’s automation strategy has been about consistency and culture, two elements that effectively feed off each other in a virtuous cycle. As one improves, so does the other.

About Consistency

Today, Metalworks has more automation and more employees than ever. Since 2020, it’s doubled its headcount, from 100 to 200 employees. Its revenue has more than doubled, from $20 million in 2020 to $48.5 million in 2022, so, yes, its sales-per-employee metric is certainly higher than it was.

The metric hasn’t skyrocketed upward, though, so to say automation has allowed Metalworks to “produce more with less” is a bit of an oversimplification—especially considering all the different jobs the fabricator processes. And therein lies the rub: High-product-mix operations are inherently variable, and that variability can get worse as the operation grows. Well-planned, efficiently integrated, and well-supported automation reduces that variability.

“It’s like the tortoise and the hare,” Ernesti said. “Welding robotics aside, people can often outpace automation, except over time.”

In this instance, he’s referring especially to material handling automation in several areas of the fab shop, including parts-stacking automation in cutting and the robotic press brake in the forming department. Watch employees denest and stack cut parts, or perhaps bend a series of brackets on a modern electric press brake. Next, watch a robot or other mechanized system grasp and stack parts, and carry a part through a bend cycle.

“A good operator could outpace the machine, especially over a short run,” Swanson said, “but over time, the robot just keeps on producing.”

A row of robotic bending cells at Metalworks produce small and large workpieces. Since about five years ago, the operation has designed and integrated its own automated systems. Images: Metalworks Inc.

Yes, the robot always shows up and never takes breaks, but the real advantages come with consistency. Ernesti recalled one brake that seemed especially rough on tooling. Specifically, the die shoulders became worn, which altered the workpiece position slightly and threw off the precision air bending operation.

“The operator would rock a specific workpiece on the die,” Ernesti recalled, adding that he didn’t blame the operator; for this application, positioning the part perfectly for precision forming wasn’t easy. “We found that this particular operation was much more consistent in the robotic press brake, which presented parts in the exact same manner every time.”

He added that automating that job just wasn’t a matter of volume. In fact, with today’ quick-changeover and offline simulation technology, job volume is less of a factor than it once was. The nature of the job matters more. Does the job make best use of Metalworks’ talent? How people answer that question dictates whether to automate or not.

Say a job involves a series of medium-volume brackets, each requiring just a single bend, along with a larger quantity of complicated pieces involving a multitude of part flips, complicated backgauging, and other details that would require the robot to regrip and reposition multiple times over a single bending cycle. In this case, Metalworks could decide to automate those medium-volume brackets while devoting those complicated pieces to several manual bending cells. The complicated piece might require custom grippers, and even if it didn’t, the robot would need to reposition repeatedly. Yes, the piece could be automated, theoretically, especially considering the fact that programming isn’t as complicated as it used to be, with software determining the best way to present blanks and stack formed parts. Still, the operation wouldn’t make best use of the company’s talent.

The last thing an experienced brake operator wants to do is stand or sit in front of a brake for hours bending one simple part after another. They want those complicated pieces, especially those where they have no trouble repositioning consistently against the backgauge—no struggling to steady a large workpiece, no rocking heavy pieces against tooling and prematurely wearing dies. In this way, Ernesti said, the fabricator’s automation strategy makes processing more consistent and, again, makes best use of available talent.

‘Don’t Spill the Tape Tray’

In this sense, ever-improving consistency has gotten Metalworks (and other fabricators like them) to where it is today. The company’s roots go back to the 1990s, when metal service centers began focusing on providing value-added services like laser cutting.

Back then, Ernesti and Swanson, ran a service center’s high-definition plasma cutting operation out of Lincoln. A noncompete agreement with one of the service center’s customers necessitated a sale, so the cutting operation had to be spun off. Ernesti and Swanson could either try to make it as an independent fabricator or close up shop and move to Kansas City, Mo., where the parent company was based. The two chose the first option.

“Suddenly, we were in business,” Swanson said. “We started with nothing, really. We got a small line of credit from a local bank, and we were able to lease the equipment from our former employer until we were able to purchase the machines. Then, it was off to the races.”

The 1990s were another period of transition for metal fabrication, a time when you could still see some legacy technology, even some punch-tape-driven controllers, alongside newer CNCs.

Ernesti chuckled. “I remember we bought an old Di-Acro punch with a controller that still ran on tape, for all of $6,000. And we ran parts on that thing for a while. Most people probably don’t remember those days, but you could still hear us then saying, ‘Don’t spill the tray from the tape punch!’”

Metalworks tests an AMADA punch/laser part removal automation. The system was recently installed as part of a line dedicated to specific product families.

The fabricator dipped a toe into automation in 1999, purchasing a CO2 laser with an automated load/unload system. From there, the business continued to grow, hitting $2.5 million in about 2002.

“We then jumped to $5 million and stayed at that level for a while,” Ernesti said. “Then we jumped to $10 million, then $12 million, and we stagnated.”

Revenue continued to grow slowly after the company put in its first forming robot in 2008. By 2018, though, the company’s automation effort cranked up a notch. At the time, the company had just a handful of robots in welding and forming. Today, it has more than 20—including an impressive row of robotic forming cells.

“We jumped from $17.5 million to $20 million for a year,” Ernesti said. “Then, during the pandemic [in 2020], we actually doubled in size. I told the guys, ‘The companies that shrink back in fear during this time will lose. Those who put their chin into the wind will come out a winner.’”

How to Automate—Now

Ernesti and Swanson both conceded that, of course, putting one’s chin to the wind does involve risk, but it’s a risk Metalworks has endured despite making a few bold moves. First, the company brought the integration of automation in-house. The decision boiled down to lead times. Customers were demanding parts yesterday, and the fabricator just couldn’t obtain the technology it needed fast enough to satisfy demand. Technical worker shortages had reached every area of metal fabrication, not to mention the supply chain problems, and managers knew they needed to find a faster way to bring in manufacturing technology.

So, they took matters into its own hands. They purchased robots. They invested in 3D printing technology to speed weld fixture and bending robot gripper design and production. 3D printing also offered design flexibility, like the printing of weld fixtures with internal channels to support pneumatic clamping.

“A few of our engineers launched the initiative,” Ernesti said. “We started with small bending cells tending 4-ft. press brake beds. We moved to larger systems with higher-payload-capacity robots. And now, we’re buying used robots and starting the integration process by ourselves.”

Having integration in-house has transformed the company’s automation approach. Years ago, an automated cell was very much project-based, reacting to customer demand or some internal need. And the return on investment (ROI) was very much time based: The more that machine ran over a shorter period, the faster its ROI.

Now, though, the company’s automation engineers think proactively and broadly. To illustrate, Ernesti described how the company recently found a 7-axis robot with a spot welding end effector and 36 ft. of travel. It also found a counterbalanced welding head that an operator could run manually. Historically, Metalworks’ managers would have chosen the manual option. After all, this particular spot welding operation ran only periodically. The robot would just sit there idle much of the time, so why buy it?

Ernesti retorted, “I really don’t care. Can you tell me who’s going to run that spot welder when we can’t find people?”

A combination of power- and force-limited cobots form a variety of small, simple parts. Blanks are stacked, and formed pieces are placed in portable totes.

The thinking goes back to consistency and making best use of available talent. This particular spot welding application requires awkward movements. Employees could do it, but could they do it as consistently as a robot, especially as demand rises?

The same thinking goes with Metalworks’ approach to robotic weld fixtures. 3D printing carbon fiber fixtures does take some extra design effort. And Ernesti was honest—some asked why the shop was going through the trouble? Is manipulating toggle clamps really that big of a deal? But then, they asked a poignant question: Have you tried doing that all day?

“When you consider how you make life easier by hitting a button on an air actuator, integrating the pneumatics becomes worth the money,” Swanson said.

Today, robotic weld fixtures are designed to be swapped out quickly, shortening the changeover from job to job. Also, a person now is dedicated to inspecting, cleaning, and maintaining those fixtures. This goes back to making best use of available talent and, most important, ensuring automation has the personnel it needs to maintain consistent production. Manipulating toggle clamps all day is tedious and slows down the operation. Spending time inspecting and maintaining fixtures ensures that the welding automation is always ready to produce.

About Culture

“I have a mantra I say to everyone in management here,” Ernesti said. “You see a problem? It’s a management problem. It’s always a management problem. There’s no running from it.”

He made that comment in reference to the fabricator’s evolving approach to automation. “When we first started to automate, we came at it with the wrong pretense: to minimize the headcount.”

Sure, some automation might help a company grow without hiring people, but automation needs support. Recently, Metalworks hired someone dedicated to continuous improvement.

“That person’s job basically is to walk through the whole facility and question why we do things the way we do,” Ernesti said. “And one of the things we’re working on is how to get more out of our robotic bending cells.”

It boiled down to hiring automation leads who would “own” specific robotic bending processes. Process leads would not only manage day-to-day operations but also work with engineers to evaluate and perfect specific bending programs, from part presentation to the bend sequence, parts removal (in a bin or stacked on a pallet), and how those formed parts are presented to the next operation.

“For this particular case, it was a lack of recognition about what the problem really was,” Ernesti said. “Everyone’s so busy. So, we needed to have someone who could come in and really focus on the problem.”

Two welding robots work in tandem. When possible, fixture designs incorporate pneumatic clamping, with some fixture bodies being 3D printed, complete with internal channels to handle the pneumatics.

Sweeping problems under the rug, all too common when times are busy, hurts in the long run, which is why, according to Ernesti, Metalworks has worked to tackle problems head-on. Automation takes too long to integrate? Let’s integrate in-house. Automation isn’t running like it should? Let’s put an operations structure in place so problems aren’t missed or ignored.

Most recently, the company has started tackling problems associated with its legacy enterprise resource planning (ERP) platform. In fact, some of the engineers involved actually began building an entirely new platform from scratch, one tailored for high-product-mix operations with the ability to measure real-time load levels at various work centers and integrate that data throughout the organization. No longer will quoting, order-processing engineers, or department leads need to reference spreadsheets or rely on other homegrown methods just to circumvent the shortcomings of legacy software. (Those engineers have since left the fabricator to form their own company, Cortex Data Services, which still works closely with Metalworks on its software platform. Look out for more coverage on this next month.)

Swanson added that such self-scrutiny creates a good shop culture, which in turn attracts talent and sets a virtuous cycle in motion, establishing a variety of career paths. For many, working with advanced manufacturing technology isn’t a bad way to spend a workday.

No longer will someone spend years operating machines for simple part runs. Automation can handle such tedium a lot better—a mantra that remains true only if a fabricator has the internal support to build, maintain, and perfect those automated systems.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Supporting the metal fabricating industry through FMA

JM Steel triples capacity for solar energy projects at Pennsylvania facility

Omco Solar opens second Alabama manufacturing facility

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI