Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Deep-draw stamping operation keeps growing

North Carolina deep-drawing operation thrives in downturn-resistant niche

- By Tim Heston

- February 20, 2012

- Article

- Bending and Forming

Figure 1: Scotland Manufacturing stamps a product that epitomizes the deep-draw process: the filter shell.

Every day the 70 employees at Scotland Manufacturing stamp thousands of filter shells, or cans, all with shapes that epitomize the deep-drawing process. Pointing out the various press lines, Plant Manager Michael Bartell ticked off specs that, for most outside the filter-can business, would make for some eyebrow-raising height-to-width ratios. The company forms shells (or any product, for that matter) between 5 and 12 inches high, having between 3- and 5.5-in. inside diameters (see Figure 1).

Thicknesses usually are between 0.025 and 0.030 in., but the company has been known to deep-draw thicker and (another eyebrow-raising stat) even thinner. Workers also go to great effort to package filter shells, enveloping the finished cans in Bio-Corrosion-Inhibitor™ (BCI™) papers.

What’s really eyebrow-raising at Scotland, even for those in the filter-shell business, is the plant layout. The company touts that it can handle small-, medium-, and high-volume orders. The presses may handle runs from only 100 piece parts to thousands, and the layout shows how the stamping company accomplishes the feat.

The plant has coil-fed low-volume, medium-volume, and high-volume lines. Hanging over each is a sign reading, “One hour of downtime on this line costs …” and then a number (which the company kept off the record). The number by the manual press line is lower than the one by the high-volume production line, but not dramatically so. For a manual line, it produces an impressive amount of revenue per hour. This press shop knows how to get the most from the line, and it has good reasons for doing so.

A Deep History of Drawing

Since incorporating in 1979, the company has made a name for itself as a deep-drawing specialist. The plant in Laurinburg, N.C., in Scotland County (hence the company’s name), puts the stamper between Charlotte and the Port of Wilmington, close to many customers.

The Laurinburg landscape shows a visual cross section of the Old and New South. To the east of Scotland’s parking lot is a cotton field; to the west is another manufacturing plant; to the north, a military landing strip where retired commercial jets are used in training. It is one of the few (if not only) places in the world where you stand by a quiet, rural field and see a 747 taxi across a runway (see Figure 2).

Still, the company does have a significant number of customers in the Midwest. That’s why the organization’s new director of business development, Matt Hunt, is in Indiana, within driving distance of many customers. Scotland’s broad geographic reach shows how in demand its deep-drawing expertise really is.

About 70 percent of revenue comes from major players in the filtration market. The remaining revenue comes from other niche markets that require deep-drawn stampings, including railcar brake casings as well as residential chimney caps. The company also has a toehold in the flat stamping arena.

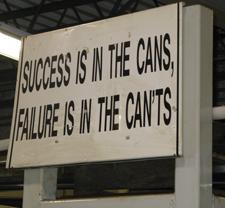

Over the decades the principal revenue driver has remained filter cans, and a sign posted near the tooling area reflects this (see Figure 3). And it is the nature of customer demand in the filter-shell business that led to Scotland’s versatile plant layout.

Diversification and Differentiation

Scotland’s employees know deep drawing, a metal forming process not for the inexperienced. “Our seasoned veterans in the tooling and engineering departments know the limitations on what you can do to the material without breaking the workpiece and pushing it over the edge,” said Hunt. “Deep drawing is a niche that has a long learning curve, and we’ve been finished with the learning curve for quite some time.”

Figure 3: A sign near Scotland’s tooling department shows how important filter cans are to the company’s revenue stream.

Over the years company managers have developed relationships with their metal suppliers, who deliver to Scotland just-in-time. Scotland receives coils a few times a week, and it doesn’t take long for them to be mounted and fed into a press. The coil storage area takes up a sliver of the 50,000-square-foot shop floor.

Scotland’s suppliers also know the idiosyncratic demands the deep-drawing process puts on a sheet of metal. Scotland receives metal certified to have a narrow tolerance window when it comes to elongation. The narrower the window, the more consistent the metal’s elongation characteristics, and the more predictably it stretches. The metal also must adhere to certain consistency requirements when it comes to hardness and thickness. Some workpieces flow into seriously deep cups over several die stations. The metal stretches significantly, and material properties that aren’t just right can wreak havoc on the process.

Another advantage again comes from that manual press line, which essentially allows Scotland to take on lower-volume jobs that others wouldn’t bother quoting (see Figure 4). The manual press line has multiple stations and makes strategic use of conveyors between presses. The conveyors themselves are on wheels, so workers can remove them quickly to bring in a cart and perform a die change.

Sure, parts flow faster off the company’s production press, a 600-ton Niagara with a multistation progressive die (see Figure 5). The behemoth press also can draw thicker and larger stampings than its manually fed, smaller counterparts. But it’s a tighter race than one would expect.

This has opened the door for Scotland to quote work from other industries—including the chimney cap business and other sectors that order relatively low volumes—but it has been equally (and perhaps even more) beneficial for its filtration customers. The stamper’s customers must be ready to supply myriad filters for older models of various pieces of equipment. The machine may have been sold decades ago, but it still needs a periodic filter change.

New machine models—be they tractors, pressure washers, or anything else—may be produced in the tens of thousands. But the low-volume (or “long tail”) products—the replacement filters needed for the thousands of models sold over the years—are the real bread and butter of Scotland’s filter business. A machine sold decades ago may have come with a lifetime service package of some sort, and with maintenance comes the need for filter changes. The customer may need only 100, but they’re needed all the same—and quickly. And if Scotland made the filter shell before, it more than likely will have the tooling available now.

This long tail of medium- and short-run stampings is where the manual stamping line plays a key role. Not only does it allow the company to quote lower-volume work, but it also gives the shop floor some flexibility. If a production line must be shut down for periodic maintenance, work doesn’t grind to a halt. Instead, after a quick tool change, the presses on the manual line help absorb some of the capacity. This maintains throughput and helps the company meet delivery deadlines.

Scotland designs and machines most of its stamping dies and other tooling components. This helps the company develop tooling for new products, using design of experiments (DOE) to perfect the tooling and get the most out of the deep-drawn material for specific products. Scotland puts these new products through conventional production part approval processes (PPAPs). And it performs statistical process control (SPC) and other documented quality processes typical for those that meet ISO 9001 and other industry standards. It also offers certain value-added services, such as hardware insertion for hose connections (see Figure 6).

“We have a lot of current projects going on right now where we take opportunities or cost-reduction ideas to our customers … be it with material, process improvements, or additional operations we can do here that would save customers time,” Hunt said.

Another differentiator is the variety of metal Scotland forms. For filtration customers, the stamper works with either tin-plated or cold-rolled steel. Which metal a customer chooses depends on the filter manufacturer’s requirements and in-house processes. For instance, if a filter company already cleans shells as soon as they arrive, cold-rolled steel may be the best option. If they don’t, tin-plated material may be the most cost-effective.

Regardless, managers said that over the years Scotland’s engineers have developed and perfected the stamping parameters to deep-draw both kinds of metal. The company also has experience drawing aluminum as well as various specialty metals, including brass.

In a sense, the filter-shell business has its own layer of diversification. After all, equipment from a cross section of industry needs filters—from oil and gas to the heavy equipment, agriculture, and automotive sectors. And unless the entire economy comes to a grinding halt, tractors, trucks, and capital equipment still need to run in the morning, and that means they need filters.

But as President Dafnie Driscoll explained, Scotland still is working to expand further into other areas, including flat stampings, as well as deep-drawings for other products. For one customer, Amsted Rail, Scotland redesigned an inner casting of a railcar braking system so it could be made out of deep-drawn sheet metal. Today between 30 and 35 percent of company revenue comes from sources outside filtration, and managers hope to raise that percentage in the coming years.

A Countercyclical Business

According to the company Web site, between 2001 and 2009 company revenue more than doubled, from $8 million to $20 million.

Driscoll then made a rare statement for most stamping industry executives: “During the downturn, we had our best couple of years.”

Aftermarket filter suppliers make up the lion’s share of Scotland’s business, but whatever the tier, filter sales tend to do well during tough economic times. When the economy improves, vertical integration at filter-makers may increase slightly. As Driscoll explained, Scotland not only competes with other filter-shell companies, but also filter-makers and OEMs that bring filter-shell production in-house. In good economic times, manufacturing managers may be less gun-shy about making the major capital investments to bring deep drawing onto their own plant floors.

Hunt added that end users tend to adhere to maintenance schedules better during an economic downturn. With minuscule capital spending budgets, companies need to make their existing equipment last longer. “We have studies from the [Filter Manufacturers] Council to back this up,” he said. “During the downturn, many people never missed a scheduled change of a filter. That’s huge for us.”

Between 2008 and 2011, Scotland’s revenue increased year-over-year by more than 15 percent. Driscoll attributed some of that growth simply to the filtration arena’s countercyclical nature, but a lot of it comes from the company’s versatility when handling various materials and job volumes.

Hunt added that, even in good times, not many manufacturers choose to bring filter-can deep drawing in-house, and if they do, it’s not a process that’s easy to learn or integrate quickly. Moreover, the cost of buying a can for a filter is minuscule compared to the remaining filter elements.

For most, outsourcing the shell’s deep drawing is much more cost-effective—and this, of course, is central to Scotland’s success.

A Big, Small Company

Whatever the broader economic conditions will be, Scotland Manufacturing’s managers have their eye on organic and inorganic growth, and this may include some bolt-on acquisitions—companies that offer products that complement Scotland’s core competencies.

This is where being part of a bigger organization can help. Scotland is the oldest member company of The Reserve Group, an Ohio-based private equity organization that specializes in small and medium-sized manufacturing companies. Member company Superior Fabrication in Kincheloe, Mich., specializes in heavy fabrication. Spartanburg Stainless Products in nearby Spartanburg, S.C., specializes in steel and stainless steel stampings for the automotive and lawn care markets.

As President Dafnie Driscoll explained, Scotland and other firms under the private equity firm’s umbrella operate as autonomous business units, but all companies do conduct business under oversight from the group’s board.

“It’s a very high-level oversight,” she said. “We’re part of The Reserve Group, which is about a half-billion-dollar company. So we have the luxuries of being part of a much larger business, while offering attention to detail and customer service of a smaller business.”

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

How to set a press brake backgauge manually

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Hypertherm Associates implements Rapyuta Robotics AMRs in warehouse

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI