Senior Consultant

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Establishing a die preventive maintenance program, Part I

Starting out with metrology

- By Tom Ulrich

- November 1, 2013

- Article

- Bending and Forming

Figure 1: Front-end information collection and inspection as part of a die preventive maintenance (PM) program keeps the presses running and the metal forming operations much more productive.

Editor’s Note: This is the first part of a two-part excerpt from Die Tooling: Preventive Maintenance for the Sheet Metal Stamping Industry. Part II, which focuses on developing a skilled workforce, will appear in the January/February 2014 issue of STAMPING Journal.

When you are planning to implement a comprehensive, die-related preventive maintenance (PM) program, the best approach usually is the easiest one. Look for the most egregious failures, and you will easily identify the problem. However, don’t expect the problems to speak for themselves.

To find those problems, your first step is metrology—collecting data by taking measurements. You need to gather basic facts before altering any situation, because your entire PM program eventually will be measured against the initial data you gather. Collecting a lot of different information that relates to various aspects of the manufacturing process is a good idea (see Figure 1).

Take into consideration any criteria that affect, or are affected by, the condition of tooling being run through a manufacturing process. The most seemingly inconsequential information can take on a new dimension when it is compared to data from an improved, in-control manufacturing process.

And there’s no need to wait for the PM program to begin—preliminary data collection can provide a baseline from which to measure the success of the overall program, and it can help you work out problems before you have the pressure of a running responsibility. It also can help you show management why a full die PM program is necessary.

Where Do I Start?

Customer Complaints. The first step is to ask your customers about their overall satisfaction. Find out the ways in which the product does not fulfill their expectations. Perhaps it’s inconsistent form, burred edges, missing holes, dirt pimples, liquid deformations, or marked panels. Then keep track of all the complaints. How many complaints do you receive per day, per week, and per month? How severe are they? Do they stop the process flow? Do they require time-consuming adjustments to fix?

Categorize each piece of information and, if possible, code it for reference and sorting purposes. This might seem tedious during collection, but the compiled data can speak loudly in favor of implementing a PM program. What manager does not enjoy reporting that the customer has realized an actual 25 percent reduction in manufacturing and product complications, or that the end user saved x hours of labor cost because the system didn’t need alterations? Whether customers are internal or external to the plant, they want to get what they are paying for.

Dock Audit. A dock audit is the final quality check before product leaves the plant. While the goal is to catch every failure by this point, the inspection isn’t foolproof, because many failures are waiting to leave the plant.

What Should I Measure?

Downtime. Downtime is one of the most important measures of manufacturing success or failure. When presses stop, production stops, and costs can accumulate rapidly. This measure is so effective that you can justify introducing a comprehensive PM program solely upon the costs and/or savings calculated from measured manufacturing downtime. Armed with a list of simple codes that describe every type of system failure and the willingness to record each incident that causes the process to stop, you can compile basic data that will give you an accurate picture of any manufacturing system’s effectiveness.

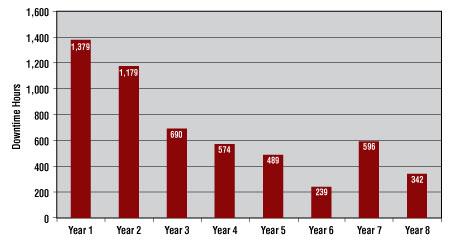

The downtime chart in Figure 2 was compiled from data collected by production control software that encompassed 28 major press lines. The presses and resident tooling stamped out framing members, interior body panels, and skin body panels. The red bars show average monthly downtime hours relating to a variety of die failures.

Figure 2: This chart shows the average monthly downtime hours relating to various die failures on 28 major press lines in a stamping facility. The presses and resident tooling stamp framing members, interior body panels, and skin body panels. Note that in the seventh year, a general foreman took charge in the die room on the lead shift when he came from the midnight shift. Because of his responsibility for the new product launch, he took almost every diemaker from PM and used them to support the launch. The PM program suffered immediately, and hours increased dramatically. Year 6 was the first year that every die was in the PM program from birth. The results of the fiasco in year 7 are clear to see during the ensuing years.

If managers are not open to a comprehensive PM program, diemakers might be dissuaded from collecting data that is most relevant to understanding overall manufacturing effectiveness. Often, though, an understanding of the data’s importance is all that’s needed to force managers and their data recorders to be accurate and fair.

Consider what can happen, for example, when the die room is charged with the previous day’s downtime caused by an automation failure. First, the die supervisor will read the report and see that his area is being charged unfairly. Then he will walk to the stamping line and challenge the production supervisor based on the erroneous information that is now part of the general plant production history—and that will now reflect unfavorably on the efforts of the die room. After making many apologies, the people recording the information will be a lot more careful about what downtime is charged to which department.

Uptime. Uptime is the time that your process is operating and producing quality parts. Use it in conjunction with downtime so that failures can be remedied and processes can be improved. Uptime really reflects the reliability of a process. In that context, the simple comparison showing increased uptime will be an effective, albeit general, measure of process reliability.

First-time Capability. First-time capability (FTC) is the ability of a manufacturing process to produce a salable product from the first cycle of the equipment, without further adjustment. Many factors work against achieving FTC, such as presses, automation, tooling, material control, racking, and transportation.

FTC can measure the effectiveness of these factors and be combined with a downtime program to achieve an effective measure of reliability.

Last-panel Analysis. Last-panel analysis (LPA) is an inspection of every final panel off the line before die set. Checking the form and the dimensions of the final panel can give you a fairly accurate picture of the condition of the tooling, and it can be the impetus for sending the dies to the die room for adjustments.

LPA can keep your process in control by systematically eliminating minor problems that do not necessarily stop the presses but, if left untended, can develop into a process failure that stops production.

Rework. Rework generated by an uncontrolled production process requires valuable floor space, skilled personnel, special tools, temporary jigs and fixtures, and special handling. This might not be an ongoing measure that you collect every week, but it’s helpful to compare it on a semiannual basis.

Collect and store information, such as initial dimensions and labor hours, in a database for later use. In today’s manufacturing environment, where cost-justification analysis is regularly applied, constant reminders of program effectiveness are essential to ensure the continued success of die PM and the resulting benefits to bottom-line profits.

Run-to-Run. The amount of time between when the last panel of a production run is placed in a rack and when the first panel of the next production run is placed in a rack is called run-to-run. Achieving world-class run-to-run times is necessary to remain competitive with other manufacturers. The run-to-run time should be less than 10 min.

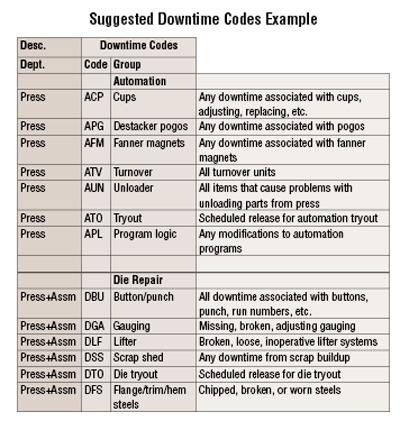

Figure 3: For statistical purposes, incidents of downtime need to be coded. Those codes can come from a list like this, or they can be customized by the stamping plant.

Knowing what causes increased run-to-run time is essential. Having well-maintained and working dies does not help if process automation is causing damage or badly forming a panel that will not pass inspection. The more details you know about your process, the better.

Panel Storage. If your plant has not already achieved just-in-time (JIT) capability, you need to measure the plant floor area devoted to panel or part storage. Floor space carries an actual cost per square foot—and everyone understands cost and its relationship to profit.

The total area occupied by fill panels or parts is an effective measure of the reliability of the stamping dies and the entire stamping process. When the process is not reliable, this extra product must be stored to provide fill. When a manufacturing line is down for repairs, fill from storage can be sent to the customer so that their production process may continue.

While it’s true that everyone stores and uses fill panels and parts, the measure is how many racks, or days, of panels are necessary. The goal should be a 24-hour supply—enough to provide the time necessary to make other arrangements should a catastrophic failure occur.

If you record this type of storage properly at the beginning of a PM program, it can give you another indication of program effectiveness and long-term benefit to the entire operation.

Throughput. The simplest measure to use as an indicator of PM success is throughput. How many panels or parts were produced this run? How many were produced last month? Last year? Reliable tooling increases throughput. To prove that premise, you need to capture current production figures and record them for later reference and comparison.

Variability. If your presses, automation, and tooling are maintained properly, and if the sheet metal is of consistent quality and dimension, your parts will be cookie-cutter perfect from start to finish and from run to run. In other words, you want to eliminate any variability, and to do that, you have to measure it.

You can use FTC, LPA, or any other quality check to measure variability.

What Do I Do With All These Measurements?

Your company will be entering a lot of data into a computer database for your PM program. Assigning a code—a term, acronym, phrase, or symbol to designate a recordable event—to each failure will help you sort and identify them and then initiate corrective actions. Coding also enables easy comparisons to indicate improvements in the process.

Adding details about each failure to another field of the database or spreadsheet allows a comprehensive analysis of recurring problems.

For statistical purposes, code incidents of downtime and assign an accurate amount of lapsed time. Figure 3 shows some suggested codes, or you can customize them for your plant. To make a customized list, ask the relevant tradespeople in your company to meet and identify possible causes of failure, and then devise a three-letter code for each cause.

For downtime, keep the codes general in nature, or your list will become too cumbersome and invite inaccurate entries. Downtime codes should fit on one or two sheets of paper so they can be taped to a table close to where the data is collected and recorded. That way, a downtime code and elapsed time can be recorded as soon as a failure occurs—before anyone’s memory of the incident begins to fade.

A computer is the most logical device to handle the large amounts of data a PM program generates. Many software programs are available for general PM, and some can be customized for die PM programs. If your budget isn’t large, you can design a database that will facilitate the recording and reporting of PM data.

Initially, before managers agree to the establishment of a die PM program, you might not have a computerized program available to you. In that case, you can gather baseline information using hand-written entries. Anyone with a pencil, paper, and list of codes can record downtime for a designated period of time.

How Do I Identify Actual Costs?

Once you’ve assigned a code to an incident, you need to assign the elapsed time associated with the failure. The accumulated time will become the most important measure, since time can be assigned a dollar value.

Identifying the dollar value of that is the job of your facility’s comptroller. Ask for a cost per square foot of empty floor space, and then ask for the cost of a press line that is standing idle. This overall cost would entail taxes, amortized equipment cost, heat, lights, maintenance, and debt service. Do not ask for costs associated with loss of production such as overtime and part repair. Do not even ask for the cost of a work crew that may be standing idle while a fix is being made. You just need the basic figure—perhaps the cost to operate on a holiday when no one is around and only property taxes, heat, and lights factor into overhead expense.

Before long everyone in the facility will know the value of one hour of press downtime. In fact, because the number will be unexpectedly high, the cost awareness will prompt most personnel to pay attention to their work environment and join the effort to reduce costs.

The Data Is Entered. Now What?

For data to remain accurate and effective, you should use and disseminate it in a report form every day. Expect others to challenge the data from time to time. Human error or mistakes in judgment always will arise.

Your goal is to report to management the breadth and depth of the die maintenance situation. Management will likely want to see more at first, but even one set of problem dies will quickly prove to them the efficacy of a die PM program. Solving one problem will earn you the right to take on an entire press line of dies, then two, then three, until your entire stamping operation is under a PM program.

About the Author

Tom Ulrich

28200 Ursuline St.

St. Clair Shores, MI 48081

586-943-4376

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI