President

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

The miraculous effect of spare capacity

How uncovering the right kind of spare capacity makes lead-times plummet

- By Bill Ritchie

- August 29, 2014

- Article

- Shop Management

It’s 8:30 a.m. and time for the daily production meeting at FabJobShop Co., a medium-sized fabricating company that builds custom products with variable schedules for numerous customers. Walt, the owner, is holding court with his staff, looking over the order list.

“I don’t understand it! We are running at 95 percent efficiency, everybody is staying busy, and two months ago we forecast enough capacity to meet these orders. But we are one or two weeks behind schedule, working Saturday and Sunday, and BigCo is breathing down my neck for deliveries. The president of BigCo wants me to go there and explain, in person, why we are always late. What is going on?”

Just then Herb from sales pops in to declare that Difficult Customer Corp. wants two cabinets of a new design.

“I’ve been working on this order for two years and they finally came through. If we do these right and on time, they will order 500 right behind them!”

Walt’s eyes narrow to slits as he asks, “And when do they want these, Herb?”

Herb’s voice gets softer as he looks at the floor and says, “A week from Friday.”

All the managers smirk as the master scheduler Sally says, “Yeah, right, Herb. And which job are we going to take out so we can build this latest order from heaven?”

“None of them! We need them all.”

Walt breathes deeply and says, “Put it in the schedule, Sally. We need this job since it could turn out to be the high-volume work that we have all been hoping for.”

The meeting ends with the usual haggling over which job is hotter, how they can get all this work done, and scheduling another weekend of overtime.

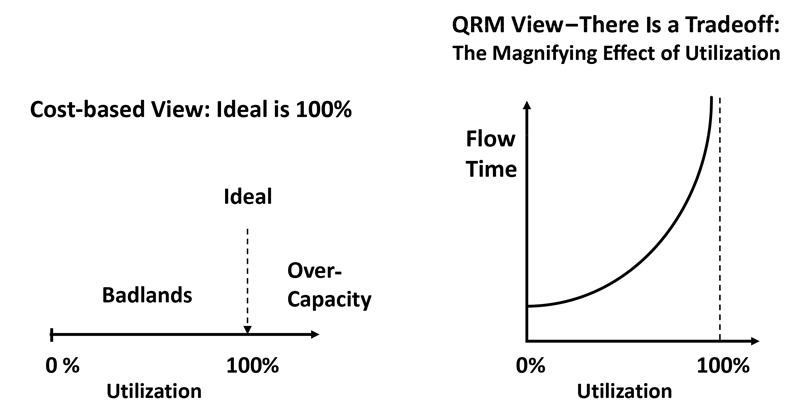

Figure 1

The cost-based approach views higher capacity utilization as ideal. In the QRM approach, tailored for high-product-mix manufacturers dealing with varying levels of demand, high capacity utilization lengthens lead-times.

While this scene is fictitious, similar meetings are being held every day in fabrication shops and manufacturing companies throughout the country. Every shop is unique, and the causes for production delays vary, but the answer to overcoming those problems begins with capacity planning.

Too Much or Not Enough Capacity

Typical capacity planning usually involves reviewing a projection of units required over a given period of time, comparing that projection to available resources, and displaying the results in weekly or monthly segments. This is done primarily to watch for one of two problems: There are too many projected orders that will cause production overloads, or there isn’t enough work to keep the machines and people busy.

A business with relatively fixed processes and steady orders often will have useful projections for planning to react to pending changes in the weeks and months ahead. This kind of business might suffer order spikes or droughts, but they tend to have better visibility than a custom shop that has variable demand. The shops that build to order with inconsistent demand typically don’t have the luxury of a dependable forecast and must design the business to meet the variability in order flow. This causes the job shop owner and managers to walk the tightrope on capacity: Do we have too many machines and people or not enough?

The problem gets worse when the enterprise owner and managers determine that the key to profitability is to keep their people and machines busy all the time. But in reality, high utilization ensures the late deliveries, high costs, and long lead-times that Walt saw at FabJobShop Co.

The Case for Spare Capacity

Rajan Suri developed Quick Response Manufacturing (QRM) in the early 1990s and published his first book on the topic in 1998. Since then he has written a second QRM book, titled It’s About Time, to further define the benefits of reducing total lead-time in the enterprise. He describes how each manufacturing business faces system dynamics, defined as the interaction of people, machines, and products. This interaction causes constant changes in the production system and puts a strain on capacity, particularly for those that have a high degree of variability in products and volume. As a process approaches 100 percent utilization, the flow rates climb dramatically. Figure 1 depicts the cost-based approach to utilization in which 100 percent is good, versus the QRM approach that shows it will lengthen lead-times through higher flow times.

Restricting capacity to try to attain 100 percent utilization does not allow any time to react to problems such as machine breakdowns, customer changes, and the natural variation that occurs in daily operations. So as flow rates climb, the operating costs climb as well in the form of expediting, overtime, inventory, customer management, and other indirect costs.

This effect of high utilization can be observed in the FJS production meeting when Walt complains that the usual cost metrics are acceptable, but they can’t ship orders on time. And he makes it worse when he relents and accepts the hot job from Herb. Sending a priority order through a production system at full capacity is like an ambulance coming through the shop with sirens blaring and all the other orders pulling to the side of the road.

When the shop is running at full utilization, all other orders in the schedule are now late—not just one order, but all of them. So then every order in the shop becomes an ambulance, racing to get to the shipping dock. And it all starts over again tomorrow with a new ambulance coming through and pushing aside those orders that were once the hottest job in the shop.

The goal of keeping people and machines busy does not ensure profitability. It might lower direct cost per unit but can actually raise total cost and drain cash while delaying shipments. Delivering customer orders when they need them in the shortest amount of total time is what actually makes money. The way to reduce that total time is to have spare capacity available to handle the variation that occurs in every business—but even more so in a custom shop with variable demand.

Suri recommends operating with extra capacity to handle system dynamics by strategically planning to operate at 75 to 85 percent of capacity. This will allow the processes to deal with the variation that causes delays. The reduction in lead-time will then lower the total cost of business while ensuring deliveries meet the customer’s expectations.

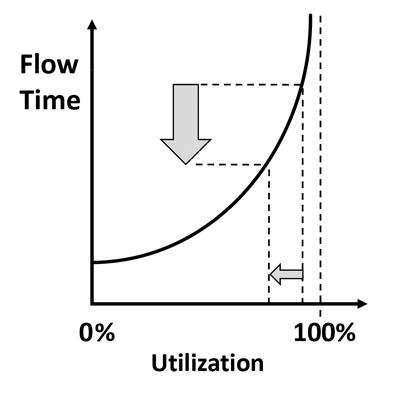

Figure 2

Spare capacity can have a miraculous effect. A relatively small decline in utilization generates a significant

reduction in lead-time.

The right amount of spare capacity required to reduce lead-times to an optimal level is ultimately the decision of the business managers who must determine how many orders they need to cover versus the resources required. Fortunately, increasing capacity does not always mean investment in expensive capital equipment; numerous other approaches should be investigated first.

Creating Capacity Throughout the Enterprise

The good news is that relatively small amounts of added capacity can make a big difference in lead-time reduction. Figure 2 shows what Suri calls the “miraculous effect of spare capacity.” Because the curve is quite steep as utilization approaches 100 percent, a relatively small decline in utilization generates a significant reduction in lead-time. This provides a great deal of opportunity for FabJobShop Co. and all variable-demand businesses. The following actions can help create spare capacity.

Business Policies. The quickest way to create spare capacity is to examine the operating policies of the business. Practices such as running extra parts on a setup to attain lower unit cost will prolong lead-times. While that policy may enhance the utilization metric, all it is really doing is turning cash into inventory while delaying shipments. And, really, how much money is the company making while people produce parts that no one needs while customer orders are sitting there on a pallet and waiting to be run?

It is important to think through the actions necessary for reducing lot sizes rather than just cut them in half and hope for the best. Setup-time reductions, tooling, and cross-training may be needed to reduce lead-times on key equipment. But as Suri has illustrated, the compilation of relatively small amounts of change can have a significant impact on lead-time reduction.

Consider the Entire Enterprise. Every process in the business can have an impact on lead-time, from customer contact to delivery of everything the customer expects. It is common to find that most of the lead-time in product delivery occurs in upfront or office operations, particularly when a custom order requires significant customer interactions and engineering design. Yet those processes are rarely measured and addressed for their effect on total lead-time. Even a business that has repetitive production processes can find that the incoming order rate is highly variable and could struggle to handle the office workload without spare capacity.

It’s About Time contains an extensive description of Quick Response Office Cells (Q-ROC). One way to begin in the office operations is simply to track the time it takes to process an order from its receipt from the customer to its release for production. Most managers are surprised to learn how much total time it takes, especially when comparing it to the touch time applied to do the work. And all time is not created equal; reducing that time upfront is significantly more valuable than the time at the end of the process, when the product is already late and waiting for shipment.

People—the Most Flexible Resource. One of the easiest ways to add capacity is through effective use of employees. That might mean hiring a person to unload machines so a skilled operator can perform more setups, or it could mean cross-training an operator to do multiple jobs on key equipment. Further benefit comes with organizing them into self-directed work teams that take ownership of a product family in the shop or office. And people can do various things during slow order periods, such as required safety training, communication meetings, cross-training, preventive maintenance, and 5S projects.

The idea of adding wages to create spare capacity can be very hard to accept for owners and managers who have always had the cost-based mindset that keeping people busy is the only way to make money. But the return on the investment of a person can be substantial when considering the benefits of better throughput and flexibility.

The leaders of a high-velocity enterprise that uses QRM realize that turning an order backlog into shipments and cash go beyond the fear that the company might run out of work—and they recognize the opportunity to produce the next order today.Align Metrics With Lead-time Reduction. Judging worker performance with a utilization metric can cause behavior such as running large batches or skipping over orders to run work that is more efficient. These actions will stretch out lead-times and cause added expense while using cash.

Even using on-time delivery as a metric can cause people and suppliers to promise the worst-case dates in order to give themselves as much time as possible. So it is preferable to place the most importance on lead-time reduction as the primary performance metric. This helps avoid actions that might improve certain metrics, but can actually add to overall lead-time.

Capital Equipment. When it becomes necessary to add equipment to meet demand, it is important to look beyond unit cost output and consider the impact on total lead-times. The strategy of time might require smaller, more nimble pieces of equipment that could be dedicated within a product cell. Large machines that produce big batches of products may not be appropriate for meeting customer needs.

Get Fast and Then Sell the Speed

QRM is a strategy that calls for the people and processes throughout the entire operation to focus on reducing lead-time at every step in the business. This requires having enough capacity to handle the variability in order flow.

Rather than spending time on implementing more accurate forecasts or extensive variance reports, become faster. Design the operation for where you and your markets are going, not where you have been. The old days of high inventory and price competition are giving way to the companies that can deliver in the least amount of time.

Picture Herb in Walt’s office at FabJobShop Co. a year later, after implementing QRM: “Wow, this is great, Walt! Customers aren’t complaining like they used to. We are hitting our delivery dates, which are way better than the other guys,’” explained Herb. “And that new quote cell is great! One customer told me that we shipped that complex box faster than the shop across town gave them a quote!”

Walt smiled and said, “Yeah, a year ago I would never have imagined how much we could reduce our lead-time. We all had to convince ourselves that adding some capacity in key areas was the answer to improving our lead-time and deliveries. We are doing even better now by making changes throughout the business to get everyone focused on reducing total lead-time.”

“And I am sure you don’t miss those old production meetings, do you?”

“No, not at all,” Walt said. “That is what we would be doing right now instead of sitting in here. Now we just do a quick stand-up in the shop each morning and rarely talk about the schedule. But now that you’re here, there is something I want to talk with you about.”

Herb sat up a little straighter. “Uh, what’s that?”

Walt looked at him and said, “We have taken the steps to change our delivery promises to shorter and shorter times. And now that we are so much faster in delivery, we need you to get out and sell orders to those people who used to tell you we took too long. And find some new markets and products that are time-sensitive. You need to reduce your lead-time, too, Herb. It is time for you to go out and sell our speed!”

About the Author

Bill Ritchie

P.O. Box 41171

Dayton, OH 45441

937-630-3035

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

AI, machine learning, and the future of metal fabrication

Employee ownership: The best way to ensure engagement

Dynamic Metal blossoms with each passing year

Steel industry reacts to Nucor’s new weekly published HRC price

Metal fabrication management: A guide for new supervisors

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI