Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

How to build a little of everything, every day

The story behind Legrand’s lean journey

- By Tim Heston

- August 6, 2014

- Article

- Shop Management

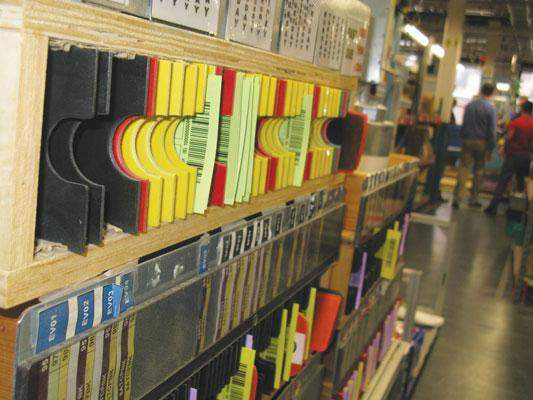

Figure 1

Legrand adapted this heijunka box, a visual scheduling tool, to accommodate a pull system in a high-product-mix environment.

When driving to Legrand North America’s headquarters, you can feel lost, at least for a moment, and then comes the nostalgia. It’s not in an industrial park or in the middle of nowhere, where land and the overall cost of doing business can be relatively cheap. It’s in West Hartford, Conn., behind a tree-lined neighborhood with a few houses that look about as old as the factory itself. Some of the earliest buildings on Legrand’s five-building, 270,000-square-foot campus go back to 1929. Leaving after the end of the first shift, I saw some workers strolling home—an original mixed-use community before the suburbs and superhighways changed everything.

In many other towns, especially in the Northeast, this neighborhood wouldn’t be so vibrant. The high cost of doing business would have shuttered the factory decades ago, and the community would have declined along with the public schools. But residents have enjoyed good neighborhoods; quality public schools; and an extremely successful employer, a manufacturer in their backyard. The factory doesn’t make medical devices or airplane engines. It’s not full of robots and space-age decor. It has people making cable management systems: enclosures, raceways, and the like. Anything used in a commercial (and increasingly residential) building to carry data or power may have come out of one of Legrand’s North American facilities.

This includes Legrand’s Wiremold® product line, produced mainly at the West Hartford facility. The products are complex and involved at a granular level, but they’re not the clean-room, crystal-growing, silicon-wafer-making magic many associate with U.S. manufacturing. One product is a metal conduit raceway designed so that electrical wire can be run throughout a house without needing to cut into existing walls—and it’s been produced since 1916, ever since electrification began increasing demand for residential and commercial wiring.

How does this plant survive and thrive? In short, it succeeds by mirroring the customer. The company has thousands of SKUs, customers buy a small amount of most of them every day, and so the people on the factory floor make just enough to replenish that demand.

In the process they identify and eliminate waste and are able to produce additional products without buying more equipment or hiring more people. And it started from the top, when in 1991 the new CEO, Art Byrne, introduced the company to kaizen, continuous improvement, and ultimately a new way of thinking.

Training From the Top Down

In 1991 the company was still known as The Wiremold Co. After nine years of continuous improvement, the company was sold in 2000 to Legrand, at which point Wiremold had quadrupled in size and increased in value by more than 2,500 percent.

“Lean training came from the top down,” said Michael Kijak, plant manager of the West Hartford facility. “As CEO, Art conducted the training and led the first kaizen events.”

Byrne also made a promise to the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW), the union that had worked at the plant since the 1930s: No worker would be laid off because of lean. IBEW has a presence at many of Wiremold’s electrical industry customers, so it made sense for plant workers to be represented by them.

Even though some products have been around for almost a century, new products have been responsible for most of the company’s sales growth. And the space-saving continues. In 2013 alone, the company freed up 10,000 sq. ft. of manufacturing space, thanks to improvement projects, and today all of that space has been filled with cells making new product lines.

From Batch to Flow

The first kaizens focused on eliminating the process villages, such as rows of stamping presses and roll forming equipment, and rearranging everything into one-piece flow, with product flowing from one process to the next with little or no work-in-process (WIP) in between.

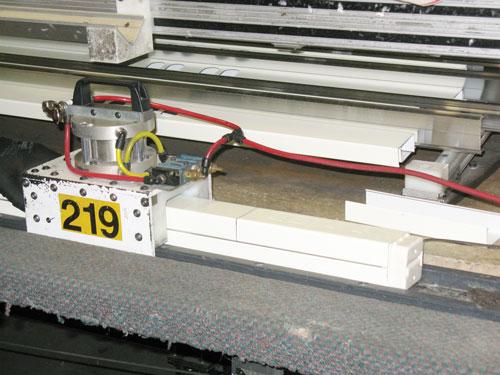

Figure 2

This unassuming air-powered hand tool, called the “squasher,” simplified the final assembly step for Legrand’s Tele-Power pole product line.

“We also focused quite a bit on setup reduction and process flow,” Kijak said. “Our goal was to make a little bit of everything, just like our customers order, so we wanted to make sure we could run and change over quickly from one job to another.”

The company reduced its number of suppliers, from a high of more than 400 to fewer than 100 today, working with many of them to spread lean philosophies up the supply chain. Moreover, the company streamlined its front-office operations. When customers ordered a warehouse item, it used to take a week for them to get it. Today that order is fulfilled within 24 hours.

“We have a lot of brain power here, and we use it. We don’t know how to do it any differently at this point. We always need to make things better,” said Kijak, starting a plant tour. Every week or so, another group tours the plant, and this one in late May included a group from LeanFab Workshop & Tours, a lean manufacturing event, hosted by TRUMPF Inc. and organized by the Fabricators & Manufacturers Association International®.

There’s a reason so many are interested. Some want to see the company’s quick-die-change system; others look at the comprehensive metrics; and most notice how effective single-piece part flow can be, even at a manufacturer producing a variety of products. Coil or blanks are fed into roll formers or stamping presses; brought through multiple operations, from assembly to painting; and then flow to a packaging station immediately adjacent to the final assembly station. Many products need not be transported between departments. If you see a pallet on the move, there’s a good chance it’s headed straight to the shipping dock.

At most product cells, packaging is where Kijak began, emphasizing the “pull” nature of the entire plant (see Figure 1). Every work center feeds parts at a pace that matches the demand of the downstream operation. It ends with the customer, the electrical distributor, which usually pulls product from Legrand’s warehouses, one on the East Coast and one on the West Coast, but sometimes orders custom products directly from the factory. About 80 percent of the company’s product is made to stock, while the remaining is made to order.

Legrand splits its myriad products into what it calls A, B, and C items. A items include products with relatively consistent demand, so the warehouse keeps only six days’ worth of products. It takes two days to make the product in West Hartford and another two days to truck it to the warehouse. That produces an overall cycle of 10 days. B and C items are demanded less frequently and less predictably, so the cycle is a little longer.

The company doesn’t shun all inventory. Having nothing on hand to make anything with or sell is a good way for a manufacturer to go out of business. But the operation carefully monitors the inventory, keeping just enough to meet the customer’s demand for immediate response. As Kijak explained, “If we’re making a little bit of everything every day, we don’t need to warehouse 20 days’ worth of products. We can just keep six days.”

From Raw Stock to Finished Good

Kijak pointed to a worker using tape and a narrow box that was folded over to package a Tele-Power® pole, a longtime Wiremold product. “We extended the length of the packaging, so now it’s just folded over and taped,” he said. “We were putting in about 6 million staples a year, which is tough on the shoulders. It saved us about 8 seconds of production time as well.” Multiply that time by the number of poles produced in a year—87,000—and you get significant savings.

The same worker that packages the product performs the final assembly step, attaching the pole components together. Previously they used hammers to get the job done, which were hard on workers’ bodies and ears, not to mention time-consuming. Not anymore. Kijak pointed to the “squasher,” what workers affectionately call “Mr. Hammer,” though it’s much quieter and easier on the shoulders (see Figure 2). An unassuming air-powered hand tool born from a simple idea during a kaizen, the squasher presses together components for the final assembly.

Raceway covers and similar products use roll formed components, and the way the plant produces them has changed dramatically. In the mid-1980s it took a 10-person crew to manage one of the lines, which entailed manual shearing; press brake forming one bend at a time; dipping parts in a large paint bath and baking to dry them; and then packaging by hand.

Figure 3

This roll forming line forms and cuts to length raceway components. The total cycle for the raceway, from raw stock to the shipping box, is now only 3.78 seconds.

“Now, with one person we’re three times as productive as we used to be with 10,” Kijak said.

Today the line uses coil stock that comes prepainted with a coating that can be formed without cracking. The material is roll formed through a series of dies (see Figure 3) and cut to length; simultaneously a smaller roll former produces the raceway base, and both components travel down a chute and drop into a shipping box with a traveler on it, which tells which warehouse the raceway is destined for. Total cycle time for the raceway from raw stock to the shipping box: 3.78 seconds.

“Last year we made a little over 2,000 miles of this raceway,” Kijak said. “One person running this cell will handle the product from raw stock all the way to finished goods. We’re pumping out $7 million worth of product a year, and one person is doing that.”

Through a series of kaizens, workers identified excessive handling and wasteful processes. The time savings it allowed greatly outweighed the higher material cost of prepainted steel. Eliminating the painting step simplified the entire operation and allowed the cycle time to shorten, shorten, and shorten some more, until now it’s mere seconds before material from raw coil stock becomes finished goods. Behind this cell is a storyboard showing illustrations of the old line, how it used to run, as well as how far the line has come.

Single-breath Changeover

Kijak pointed to a similar storyboard one building over, near a high-product-mix stamping line. The area shows just how “making a little bit of everything every day” can still apply to the traditionally high-volume world of the stamping press.

One stamping cell produces a simple base plate for circuits or communications cabling, called the Round Line. Five kaizens ago, setup took five hours. There was just one daily, and the cell ran just one SKU over a shift—classic, inefficient batch production, with eight workers handling massive amounts of WIP, which forced the cell to take up more than 1,000 sq. ft. Today material is blanked and drawn in a stamping press, followed by several secondary operations, including hole-cutting and tapping stations. One operator produces 10 SKUs over one shift, producing a little bit of everything, in just a little more than 450 sq. ft. The entire manufacturing time now takes just 12 minutes (see Figure 4).

Setup time now takes about 15 minutes, though many are far less than that. For a recent tour group, the quick-die-change team demonstrated how they can switch out dies in less than 4 minutes. And there’s a good reason those setup times are scrutinized: “We run between 10 and 15 dies every shift,” Kijak said. “Again, we run a little bit of everything every day.”

They made this happen by standardizing tool sizes and standard heights for all of the 1,200 progressive tools in the plant and using pneumatic air clamps to affix dies quickly. Adjacent to the stamping area is a diagnostic toolroom. Dies are placed on a conveyor and are inspected, cleaned, and repaired if needed. The last strip run through the press is also placed on the die, where a tool- and diemaker measures it to ensure everything is where it’s supposed to be (see Figure 5).

Each die has a report card affixed to it showing the run history, repairs, as well as any setup difficulties that might have occurred. Usage and inspection information is documented and affixed to the die itself. As Kijak described, “We have a record of any changeover difficulties. We have the day the tool ran, how many parts it ran, any problems, what corrective actions were taken, and who performed the corrective action.”

He then pointed to a series of lights overhead (see Figure 6). If an operator has a problem, he presses a button, which illuminates a light that tells a tool- and diemaker that some assistance is needed—all there so the operator can stay by his or her station and remain productive.

Figure 4

Storyboards appear throughout the Legrand plant, showing progress made after numerous kaizens.

Such changeover scrutiny has made single-piece part flow, producing just enough to meet downstream customer demand, really work in this high-product-mix environment. The same scrutiny carries over to the shop’s fabrication area, which handles smaller-volume orders and custom work. Near one punch press workers prestage all the tooling needed for the next job on a track adjacent to the machine (see Figure 7).

In one rolling mill, tools have been configured so that the operator can change over in a mere 30 seconds. “We were challenged at one time to do a one-breath setup,” Kijak said. “Between the last good part of one job and first good part of the next job, he should be able to hold his breath. And so we modified the tooling, so all he has to do is open up the guards in front and pull or push the tools, depending on [the job requirements].”

High-product-mix Pull System

Not every cell ends with a complete part. Some move from forming and fabrication to a powder coat line and then to assembly. Most stations in assembly are one-piece flow, but not every station involves a hand-off. In some areas, workers “follow the rabbit,” as Kijak called it, meaning that one assembler follows a workpiece through every stage of assembly.

All jobs flow to assembly with colored tickets that act as kanban cards, organized in a heijunka box. These cards are based on customer demand. If a customer orders an item pulled from the warehouse, that triggers a replenishment order at the West Hartford facility, and a colored ticket for the order is sent to assembly. The assembler’s goal is to keep a day ahead of the due date demanded by the downstream customer—that is, the warehouses—so tickets for Friday’s orders should ideally be completed by the end of the day on Thursday (see Figure 1 and 8).

The ticket has the part number, quantity, and processing time. When assemblers pull raw stock (the “supermarket,” in lean parlance), this triggers that stock to be replenished, either by an outside supplier or internal customer, such as upstream punching and forming. Stocked items are made immediately and sent to the warehouse, while made-to-order items—most of them slight variations of stocked items—are turned around in five days. It’s a classic pull system, but adapted for a high-product-mix environment.

Measure, Document, Improve

The entire plant abounds with storyboards showing overall progress after several kaizen events. Key metrics are posted in every department every day, including safety measures as well as on-time delivery rates for downstream customers. (The techs on one roll forming line put a large “0” near this metric, touting zero late deliveries; a little bragging never hurts.)

Each board shows the name of the cell and a variety of metrics, including how many minutes of work are in the heijunka boxes on a given day, as well as matrices for cross-training that show who’s trained on what job. In a plant with thousands of SKUs, cross-training is invaluable. Green shows that workers are fully trained, yellow means that they’re in training, red means they haven’t been trained yet, while gray means that the cross-training isn’t required due to a worker’s job classification.

Profits up, Costs Down

So what has happened since the 1990s, when the company’s lean journey began? During the first nine years sales quadrupled, inventory decreased by 75 percent, the required floor space was cut in half, and profit went up 13 times. And thanks to profit sharing and various incentive programs, workers benefited financially.

As Kijak explained, when the company was sold to Legrand, the parent company was hands-off for the first four or five years, neither promoting lean nor hindering it, but Byrne had left the company with a leadership trained well in lean principles. With any change, though, comes challenges and myriad perceptions. One book and several blogs were published claiming that Legrand had dismantled lean initiatives and returned the shop floor to a batch-and-queue model. Sources inside the company dispute this, and as Kijak put it, “We don’t dwell on it. We just tell people to come on in and see what you think.”

Like everywhere else, Legrand’s sales declined during the Great Recession, but they have climbed back sharply since 2009. At this writing, both variable and fixed costs are down, including energy (see Energy not such a fixed cost sidebar) and material costs, thanks in part to a comprehensive recycling program. Last year alone the plant recycled 60 tons of cardboard and 4 million pounds of steel. A few years ago the plant spent $100,000 just on removing pallets. So now it reuses all of its pallets, and the ones too worn for reuse are sent out for refurbishing.

Figure 5

In the toolroom, dies are placed on a conveyor, where they are inspected, cleaned, and repaired if needed. Many operations require a die changeout between 10 and 15 times a shift.

The improvement continues unabated; during the past three years the company held more than 250 kaizen events, each between three and five days long, and the events continue to pay for themselves and then some. Today profit is up significantly, at about 24 percent—a significant rise since 2003’s 9 percent profit margin. Globally Legrand sales reached $6 billion last year, and North American sales reached $1 billion for the first time ever, much of it coming from a series of recent acquisitions. Legrand now employs 2,600 in North America, and last year the 325 in West Hartford churned out $141 million worth of products.

All this comes from clear communication and documentation, good metrics, focus on ergonomics and safety, staff incentives—and producing a little of everything every day.

Energy not such a fixed cost

In 2011 John Selldorff, president and CEO of Legrand North America, had lunch with President Obama and Secretary of Energy Steven Chu. The company just became one of the few manufacturers in the country, and the only Connecticut company, to enroll in the government’s Better Buildings, Better Plants challenge.

The company has installed seven electrical submeters, each of which has about 20 nodes that measure about 140 places throughout the plant. From the West Hartford plant has developed myriad ways to save on energy. For instance, it now has various lighting controls that allow portions of certain bays to be shut off during nights and weekends, when the entire plant may not be operating.

According to company metrics, Legrand’s West Hartford facility paid $1.1 million for electricity in 2008. In 2013 its electric bill was $651,000, and sources predicted that the amount will be even lower this year, proving that fixed electrical costs might not be so fixed after all.About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI