Vice President/Partner

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Health care reform: Navigating pay or play

What fabricators can expect from the Affordable Care Act’s pay-or-play provision

- By Brian Coyle, Leon Rebodos, and Todd Soma

- October 9, 2013

- Article

- Shop Management

It has many names: “Obamacare,” Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), Affordable Care Act (ACA), health care reform—but under any name, it’s the law. Its intent is to extend health insurance coverage to millions of uninsured while also reforming the health care delivery system to improve quality and value. It also includes provisions to eliminate disparities in health care, strengthen public health and health care access, invest in the expansion and improvement of the health care workforce, and encourage consumer and patient wellness in both the community and the workplace.

According to the Congressional Budget Office, the law will increase coverage to about 94 percent of Americans. There is also hope the law will slow the rate of growth in federal health expenditures by $124 billion over the next decade.

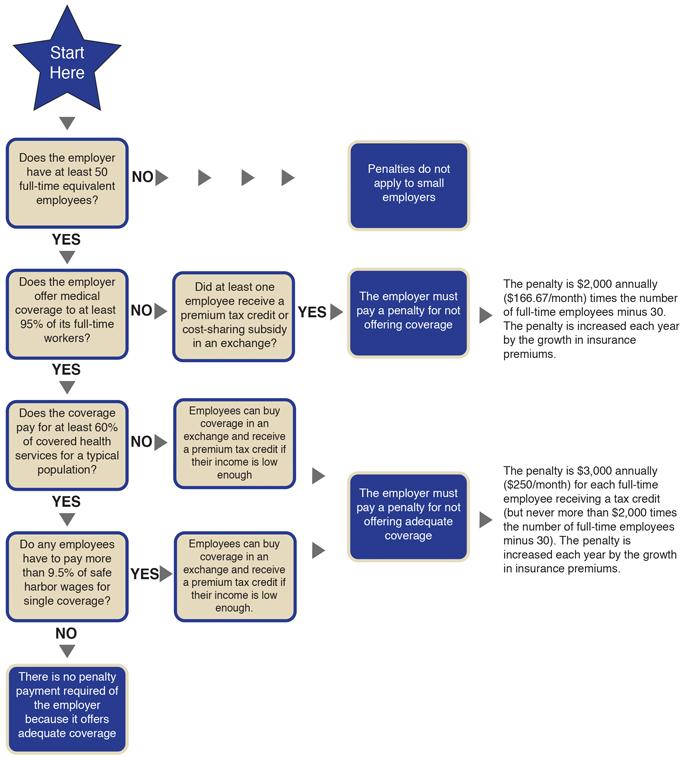

As health care reform has begun and new requirements of the law go into effect every year, the changes are hard to keep track of. For business owners, one of the most dramatic changes will be what has come to be known as the “pay or play” provision, under which many employers will need to provide employee health care coverage or pay a tax. Originally set to go into effect next year, its implementation has been pushed back a year—to Jan. 1, 2015. The Treasury Department announced that it was concerned about the complexity of requirements and the amount of time to put them in place. This delay leaves room for more changes and uncertainty.

The provision mandates that an employer with 50 or more full-time employees will be required to provide health insurance coverage. That doesn’t sound too confusing, right? Well, restate that to read what the law says: A “large employer” with 50 or more “full-time” and “full-time equivalent” (FTE) employees must offer health coverage that is both affordable and provides minimum value to substantially all full-time employees and their dependent children, or pay either a $2,000 or $3,000 per-employee penalty. That makes it all a lot more complicated.

To avoid penalties, employers with 50 FT and FTE employees will need to provide “affordable” health care coverage to 95 percent of its full-time workers—and according to the law, anyone who works at least 30 hours a week on average is a full-time employee. So what’s “affordable” coverage? According to the law, the employee’s portion of payment for individual coverage should not exceed 9.5 percent of the employee’s income stated on his or her W-2 form.

Small businesses dominate metal fabrication. In fact, it’s not uncommon for a shop to employ between, say, 45 and 55 employees, depending on the time of year, the work load, and the number of temporary and part-time workers hired during the year. It’s just the nature of the business. So according to the law, how many employees does this kind of fabricator really have? The answer isn’t straightforward.

How Many Employees—Really?

The law differentiates “large employers” from “small employers,” and the threshold is 50 FT and FTE employees. Determining company size can be simple for businesses constantly well above or below the threshold, but complex and ever-changing for employers near that threshold.

The law considers a business a “large employer” if it employed at least 50 FT and FTE employees during the prior calendar year. Considering this, it’s possible for a company to change status from a “large employer” to a “small employer” every calendar year.

An employee is considered full-time for a particular month if he works an average of at least 30 hours per week during that month. If an employee does not average 30 hours per week during any particular month, then he is considered part-time (PT) and counts on a pro rata basis as an FTE employee.

To calculate the number of FTE employees, add the total hours of service from all employees who do not meet full-time status for that month, and divide that number by 120. For example, if four part-time employees each worked 100 hours in a particular month, they would equal 3 FTE employees (100 × 4 = 400/120 = 3.33). Using this same example, say this company had 47 FT employees during that month. Adding the 3 FTE employees to that gives a total of 50 FT/FTE employees for that month.

The employer does this calculation for every month, adds every month’s number together for the entire calendar year, then divides by 12 to get an average. If the average is 50 or more, the company meets the law’s definition of a “large employer.”

As another example, say a year-round worker is hired Jan. 1 as a part-time employee expected to work 15 hours per week. A large job comes up that requires the employee to assist and put in additional hours over the next three months. The employee works 50 hours a week in October, 35 hours a week in November, and 35 hours a week in December. That employee would be considered a full-time employee for the months of October, November, and December. And the 15 hours worked per week from January to September would be added into any other part-time employees’ hours to calculate the number of full-time equivalent employees during those months.

Seasonal and Temporary Workers

The complexity continues with seasonal and temporary workers. Although neither are permanent employees, both can count toward the 50-employee total.

The law defines “seasonal employee” as one whose employment is based on a particular season—holiday workers in retail, for instance. Temporary employees hired for a few months to complete a large job would not count as seasonal because these projects theoretically could be completed any time of the year. According to the law, these temporary employees count toward the FTE total.

Seasonal employees also are counted toward the 50-employee threshold—unless the employer crossed the 50-employee threshold for 120 or fewer days during the calendar year, and employment of seasonal workers is the reason that the company exceeded the 50-employee threshold.

Change on the Horizon

Pay or play will keep HR departments busy before the Affordable Care Act provision finally goes into effect in 2015. Companies should determine whether the ACA provision applies by figuring out whether or not they employed 50 FT and FTE employees during the previous calendar year. If so, the pay-or-play provision applies. This means full-time workers (that is, anyone who works more than 30 hours a week) need to be covered if companies want to avoid penalties. For new full-time hires, the company must offer coverage no later than 90 days following the date of hire.

Further details abound about when and how companies need to offer health benefits for certain employees: for instance, those that may work more than 30 hours a week on average some months, but less during other months; or certain workers from temp agencies. Complications are abundant, and your benefits provider or advisory firm should be able to help you.

The changes that PPACA will instate have only just begun. Keeping on top of the changes and working to understand the law will be key for any company adjusting to the new health care landscape.

The Affordable Care Act: Fact vs. Fiction

Fiction: If you’re insured through your employer, health care reform won’t affect you.

Fact: On the contrary, many new consumer protections under the Affordable Care Act are already benefiting people with job-based health insurance. Some positive improvements that come from PPACA include coverage for dependents up to age 26, and zero copay for now-enhanced preventive care.

Fiction: All businesses will be required to provide employee health insurance.

Fact: The Affordable Care Act does not require employers to provide health coverage. However, the law imposes a penalty on large employers that do not offer either a federally qualified plan or affordable coverage and subsequently cause their workers to purchase plans through a state exchange.

Fiction: Health care reform creates a “death panel” to make decisions about end-of-life care for seniors.

Fact: Early drafts of health care reform would have allowed Medicare to reimburse physicians for time spent talking with older patients about advance care planning. But these provisions were eliminated in subsequent revisions.

Fiction: Health insurance is going to be cheaper.

Fact: Like most insurance, health insurance is priced on the basis of risk to the carrier. Health care costs will go down only if risk is reduced or spread out. Depending on your situation, you may not save anything. Based on the results of an insurance carrier analysis, most employers with 50 or fewer employees may end up spending more.

Part Fiction: The law requires you to begin paying taxes on your health insurance next year.

Fact: On the surface, this statement is untrue. Initially some employers that provide health insurance must begin putting the amount they contribute to workers’ health insurance premiums on workers’ annual W-2 forms. But the law doesn’t change the tax treatment of those premiums; they’re still exempt from income tax. However, certain taxes and government fees will apply to insurance carriers, insurance administrators (self-funded plans), and certain health care-related industries, and this will cause health care costs overall to increase for those who pay for it.

About the Authors

Brian Coyle

555 S. Perryville Road

Rockford, IL 61125

815-398-6800

Leon Rebodos

Vice President/Partner

555 S. Perryville Road

Rockford, IL 61125

815-398-6800

Todd Soma

Vice President/Partner

555 S. Perryville Road

Rockford, IL 61125

815-398-6800

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

How to set a press brake backgauge manually

Capturing, recording equipment inspection data for FMEA

Tips for creating sheet metal tubes with perforations

Are two heads better than one in fiber laser cutting?

Hypertherm Associates implements Rapyuta Robotics AMRs in warehouse

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI