Contributing editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Ensuring quality bent parts—from sheet to ship

How one fabricator calmed qualms with QA

- By Kate Bachman

- February 24, 2017

- Article

- Bending and Forming

Weaver Precision Fabrication & Finishing manufactures enclosures, cabinets, control panels, housings, brackets, frames, and chassis for the robotics, automation, and packaging industries.

For many metal fabricators, watching the Super Bowl is about as exciting as it gets. They get caught up in the throes of the throws, the midair leaps, the grunts, the near-misses, and the just-caughts.

For the husband-and-wife owners of Weaver Precision Fabrication & Finishing, Super Bowl 2016 was especially exciting because a halftime commercial featured yellow robots that they are very familiar with—not just as their shop tools, but as moving embodiments of their high-quality work. After all, a manufacturer doesn’t retain a customer with a Super Bowl-sized promotional spend without providing champion-caliber components.

Founded in 1945, Weaver Precision Fabrication & Finishing, Akron, Ohio, had become a successful contract manufacturer. When Jim and Marian Lauer bought the company in 1998, they assessed the company’s capacity. After all, a winning team must know its strengths and weaknesses. They determined that equipment upgrades and a formal quality program were needed.

“When we bought the company, Weaver had a great reputation and a solid customer base that was a great platform to build on, but the machinery had become antiquated,” Jim Lauer said. He oversees sales and business growth.

Today Weaver manufactures enclosures, cabinets, control panels, housings, brackets, frames, and chassis for the robotics, automation, and packaging industries (see lead photo). The company could not meet its high-tech customers’ demands for perfection with antiquated equipment and an inconsistent quality program, the Lauers determined.

“Quality is a cornerstone of our business. Most of our customers are ‘dock to stock’ with no incoming inspection of our parts, so it is vital that we ship good parts!” Jim said. “If a problem arises, it happens when the part is on our customers’ production floor. We have to ship virtually defect-free parts.”

Quality Upgrade

Company owners developed—and over time improved—an ISO 9001 quality assurance program; added and upgraded equipment; expanded capabilities to include powder coating; enlarged the facility space; and grew staff from eight to 60 employees. Annual sales in 2016 exceeded $6 million.

“ISO 9001 certification helped us greatly to strategize our process,” Jim said. “It helped our process to be reliable and repetitive.”

Marian Lauer heads up the company’s quality assurance program as well as human resources and safety. “We were first certified in 2008, as mandated by a customer. The certification provides accountability and credibility almost immediately,” she said.

“But when you’re first getting certified, you’re just learning the playbook, so you’re working for the certification instead of the certification working for you,” she continued. “Early on it was more like … you just want to get it done.”

Figure 1

Behind every good bend at Weaver is a dual inspection system. Both the operator and a quality inspector scrutinize the bent parts, and both must sign off on the part before it moves to downstream processes.

Recently the company bought a larger plant to consolidate its operations. “Now, with the move under one roof, the certification and the standards worked beautifully for us,” Marian said. The standards served the company in keeping operations organized and by requiring long-term and short-term documentation. Marian said she likes that the ISO 9001 standard requires continuous improvement, because that is in keeping with the company’s goals.

Checks at Every Step

“Quality parts and customer service define our company. Our credo is ‘Whatever it takes.’ Our customers need their parts to be defect-free,” Jim said. “Let’s say they’re attaching a cover in assembly. The holes must line up, the cover has to have the correct overall dimensions, it has to be the right color and made out of the correct material.”

How does company management know it is shipping a good part? In-process inspections are performed on the shop floor and in the inspection office using digital and dial calipers, micrometers, digital height gauges, pin gauges, taper gauges, thread gauges, angle gauges, and material thickness gauges. All of the equipment is calibrated regularly and recorded for the ISO system.

A routing record, or “router,” accompanies each job. “Every operation is bar-coded so we know exactly where a job is at any given time,” Marian said.

An approach that the manufacturer takes to ensure defect-free results is that two people—the operator and an inspector—scrutinize the first-off part independently at every operation. The operator and the inspector cannot share their findings. Both must sign off before the part can advance, Marian said (see Figure 1).

“The key to our quality program—the core, heart and soul of it—is that we perform two independent inspections at every operation, from cut programming all the way through powder coating,” she said. Here is how a part is inspected, from sheet to ship.

1. Incoming Raw Material. The quality check begins with the raw material—steel, aluminum, and stainless steel sheets. “We have an incoming inspection process to verify quantity and type are to spec,” Marian said. Vendors provide material certifications to qualify what they have delivered to the plant—that it is what they say it is, and that it meets all industry standards. The company keeps the certifications on file where they can be accessed if a customer calls and needs verification. The Lauers visit new vendors to make sure that they have quality systems in place as well.

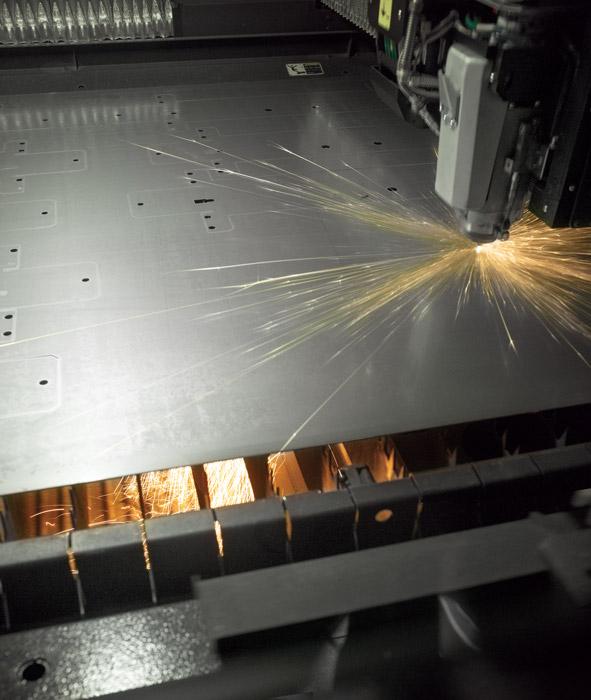

2. Cutting. When a part is programmed and sent to the fiber laser or 20-ton CNC punch press, the material’s flat dimensions are verified before the steel is cut (see Figure 2). After the laser or punch operator cuts the first piece, the cut material is counted and measured, then an inspector verifies those measurements.

3. Deburring, Grinding. Next, the cut parts are sent to the grinder for deburring (see Figure 3). “After the part comes off the laser or punch, it goes to deburring to remove burrs or dross. The grinder operator checks the first piece,” Marian said. “Then it goes through inspection to make sure it was ground off properly before going on to the press brake for bending.” Welds also are ground smooth in preparation for powder coating.

4. Press Brake Forming. The Lauers maintain that their success pivots on quality at the press brake. Nearly every part Weaver produces is bent and formed there. At the in-process inspection stage, an operator and an inspector check overall dimensions and angles of the parts at the brakes. “If the angle is supposed to be 90 degrees and the flange is supposed to be 3 inches, that is what we check,” Marian said.

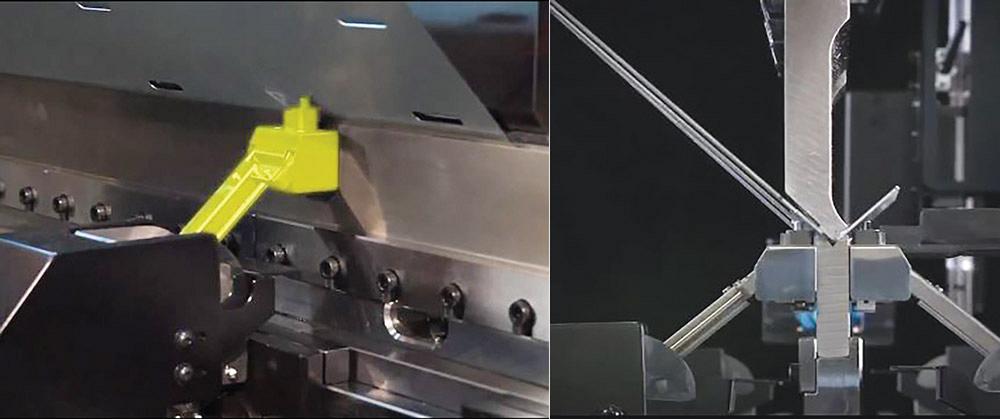

A recent press brake purchase streamlined the quality checks processes (see Figure 4).

“We bought a robotic welder three years ago,” Jim explained. “We were having problems fixturing and welding parts at the robot. A bit of tweaking was required on numerous parts, particularly with the heavier-gauge stuff.” The welders were catching and fixing mistakes made upstream. They were having to spend valuable time tapping some parts’ corners square with mallets, which was cutting into their welding time.

“We consider ourselves a precision fabricator, but the robot proved we were not as precise as we thought. We identified that the problem was at our forming process. The press brakes were not forming quality parts consistently,” he said.

The Lauers decided to upgrade their press brake equipment. As due diligence, they researched press brake equipment by visiting several OEMs’ demonstration centers. They were particularly impressed with a feature they saw demonstrated on the Amada America Inc. HG 1303, a 143-ton, downacting hybrid drive press brake equipped with AMNC 3i intelligent, interactive, and integrated controls and a bend indicator sensor (Bi-S).“The Amada brake had an automatic bend indicator that is very user-friendly. Some of the other brands had them but they were cumbersome,” Jim said.

The bend indicator sensor analyzes the bend and then readjusts automatically to apply the appropriate pressure so that the part’s bend is to spec (see Figure 5). Jim called it “the coolest part of the whole thing.

“When we first saw the bend indicator at the tech center in Chicago, we couldn’t believe how fast it analyzed the bend. It sensed that a bend was not at 90 degrees and hit it again almost instantaneously,” Marian said.

Using the bend indicator, the operator does not have to spend time checking and tweaking, Jim said. “Normally, an operator hits the blank, takes it out of the machine, puts a gauge on it, determines if it needs to be hit again, and adjusts the ram so it will come down harder or deeper or back off.”

The bend indicator is a small, sensored device. Two “arms” slide in and touch the part from both sides to analyze the bend. If the bend is not to spec as programmed, the device indicates to the press brake controller to hit the part again as needed to achieve the correct angle.

“It’s like a fancy electronic protractor,” Jim said.

The device is attached to the brake but out of the way of toolholders and backgauges when not in use. “You can turn it off and on. It springs into action, does its job, and then it gets out of the way,” Jim said.

The company purchased the HG 1303 press brake. Jim called it a “game-changer,” adding, “The bend indicator is really helpful in attaining quality bent parts. The operator doesn’t have to take out a square or hammer. He or she can just form parts and get them to the next operation faster. First part good; last part good.”

He added, “When you have to issue a mallet to your press brake operator, you know you don’t have the technology you need.”

Having the assurance that the bends have been measured and analyzed at the brake makes the quality system smoother and better, Marian said.

5. Welding. When the welder completes his or her first piece, it gets a thorough exam before it continues on to further assembly and finishing. “At the welding stage, once again, we check dimensions, type of weld, and the size and quality of the weld,” Marian said.

6. Drilling, Tapping, and Machining. At the Hurco 3-axis CNC milling center, the operator and inspector check the thread of the tap and the depth of the countersink (see Figure 6).

7. Powder Coating. After the part is powder-coated, the operator and inspector use a thickness gauge and a spectrophotometer to check that it is to spec.

After the part has been completed, it undergoes a thorough, final inspection to ensure that all operations have been completed and the overall dimensions are accurate and to the print. “The part must meet whatever specification is called for on the customer’s print within the given tolerances,” Marian said.

Reject Rate: <1 Percent

As a result of its quality assurance program, Weaver Fabrication & Finishing’s reject rate in 2016 was less than 1 percent. “We ship our robotics customer about $2 million worth of product a year, and I think we had only eight rejections in the last six months,” Jim said.

“We catch defects internally, but our external rejections, our tolerance rejections are really low,” Marian said. No harm, no foul.

The cost of defects is twofold, the Lauers said.

Figure 4

The Lauers maintain that their press brake is pivotal to part quality. Nearly every part it produces is bent and formed there. The company installed an Amada HG 1303 press brake equipped with an automated bend indicator sensor that simplified bend quality inspections.

The amount of work that goes into a rework erodes the profit line even if the part is salvageable, he said. “Not to mention the amount of paperwork generated by a rejection is very time-consuming to all involved. One of our customers charges us a cost-of-quality charge of $200 per rejection because that is how much they assess that it costs them to generate the paperwork.

“We coach our crew to take a few extra seconds of analysis on a part to make sure it is correct—that can save thousands of dollars in rejections.” He added, “We do have a great team here. We are really blessed with awesome employees who understand that.”

The cost of rejects runs deeper than absorbing part costs, Jim said. “Our top four customers evaluate us. If we have followed our quality program and we have completed our inspections, there are no issues. The part fits, the customer is happy. When the customer does not have to take the time to inspect parts at incoming, if they can be confident that the parts are good and are made to print, it saves them time and money.

“That makes us more valuable, and ties us closer to their manufacturing process. It solidifies our relationship with our customers,” Jim said. A winning strategy.

He added, “Without our quality system and our ability to deliver quality parts consistently, we would be out of business.”

Photos courtesy of Amada America Inc., Schaumburg, Ill.

Weaver Precision Fabrication & Finishing, jlauer@weaverfab.com, mlauer@weaverfab.com, 330-745-3105, www.weaverfab.com

Amada America Inc., 877-262-3287, www.amada.com/america

About the Author

Kate Bachman

815-381-1302

Kate Bachman is a contributing editor for The FABRICATOR editor. Bachman has more than 20 years of experience as a writer and editor in the manufacturing and other industries.

Related Companies

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI